“There are things that are not sayable. That’s why we have art”

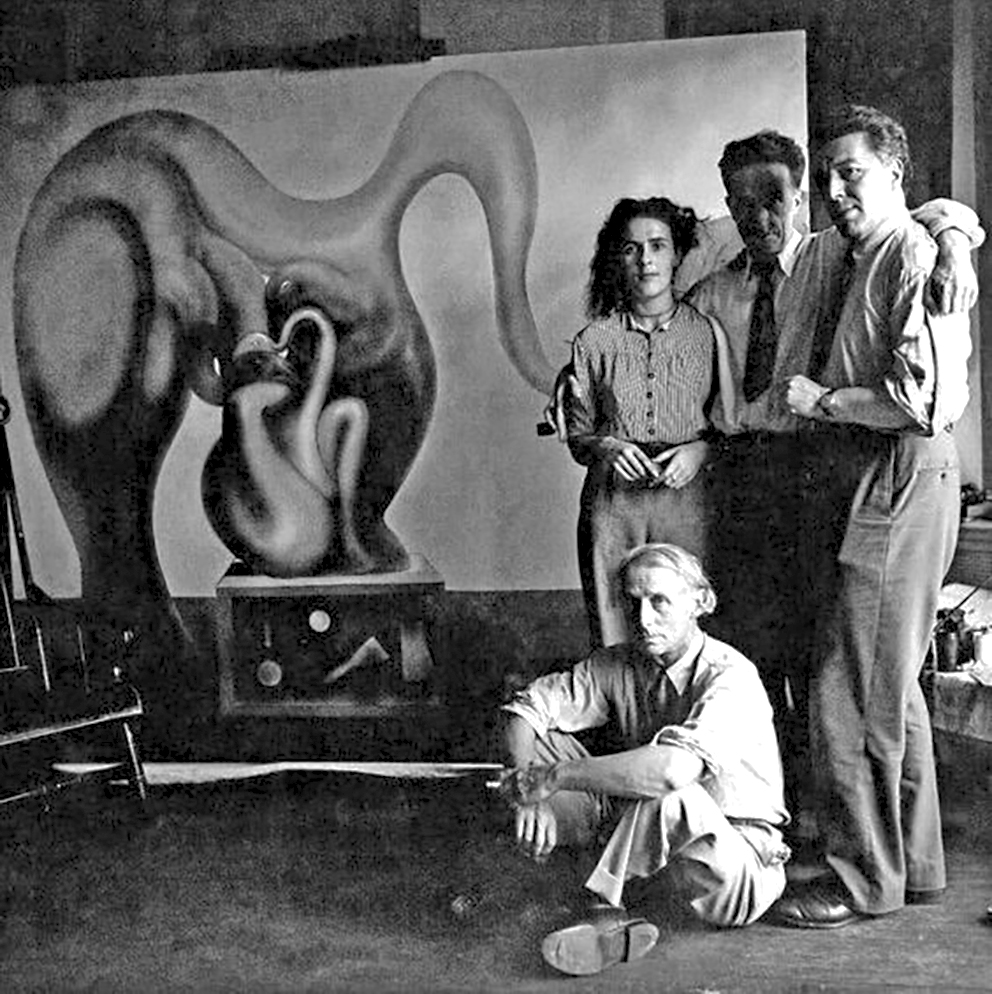

Leonora Carrington muse, soft sculpture, with ‘Leonora in the morning light’. By Max Ernst.

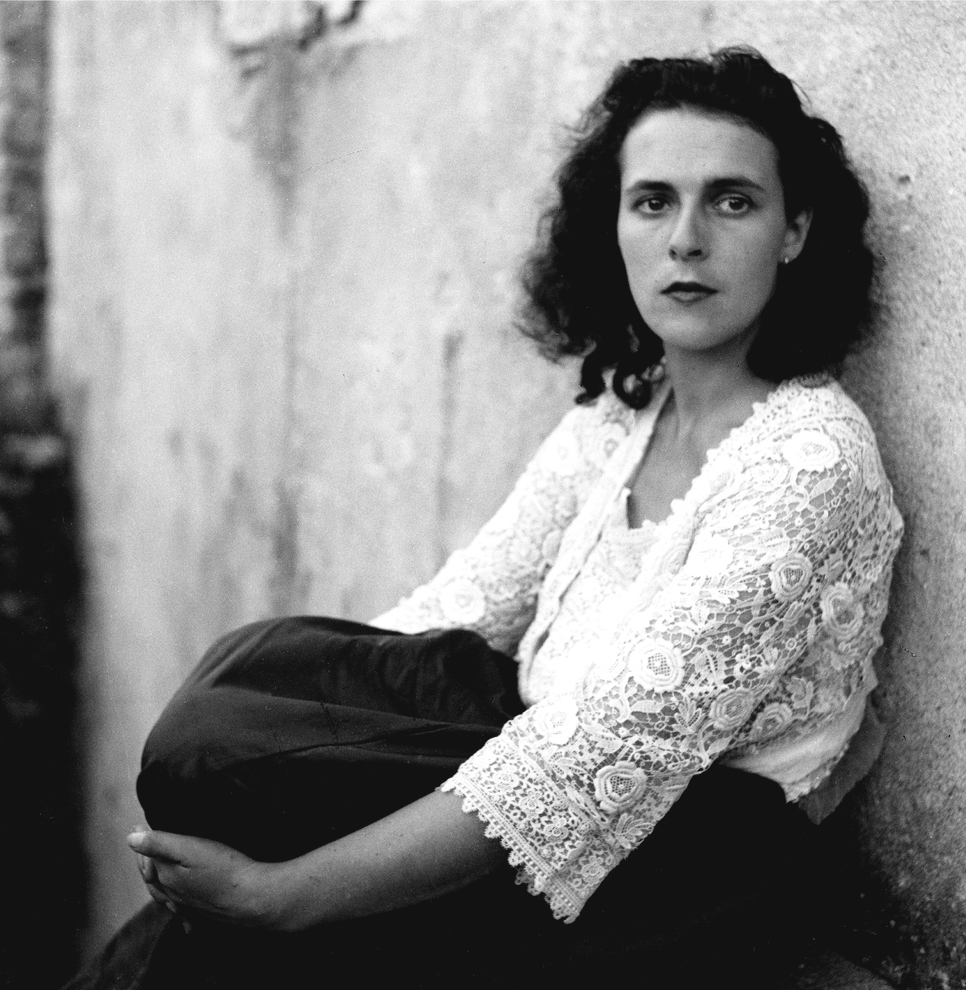

Leonora Carrington 1917- 2011

Leonora Carrington OBE, was a British-born, naturalised Mexican surrealist painter and novelist. She spent most of her adult life in Mexico City, was one of the last surviving artists connected to the Surrealist movement of the 1930s and was also a founding member of the women’s liberation movement in Mexico during the 1970s.

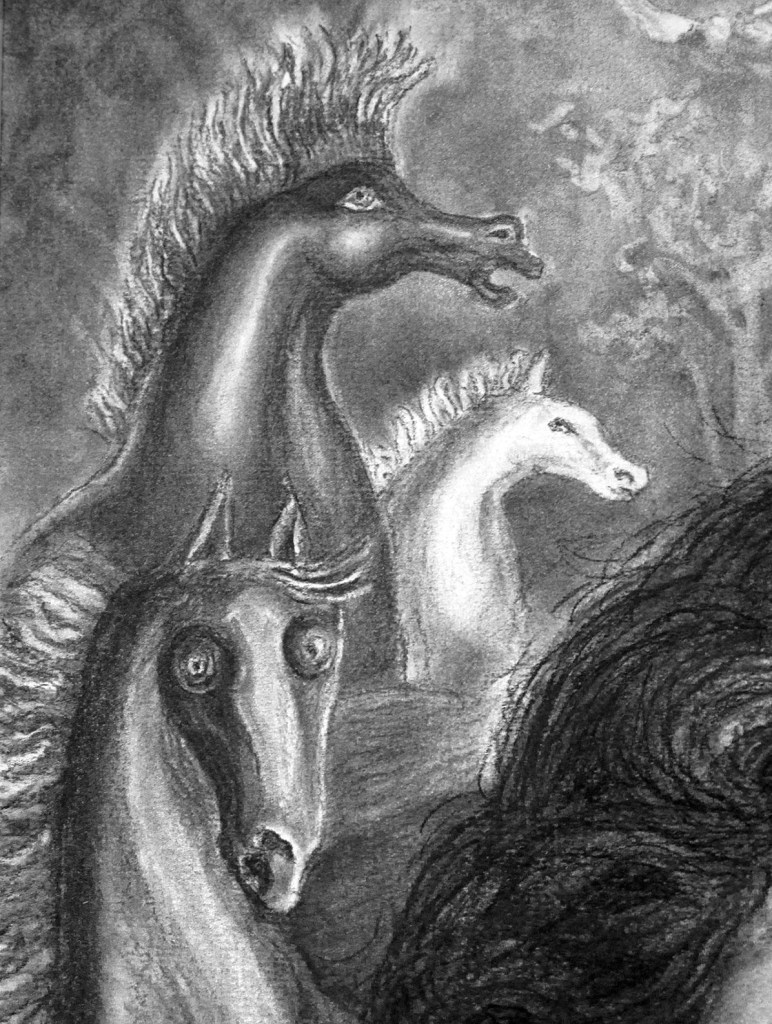

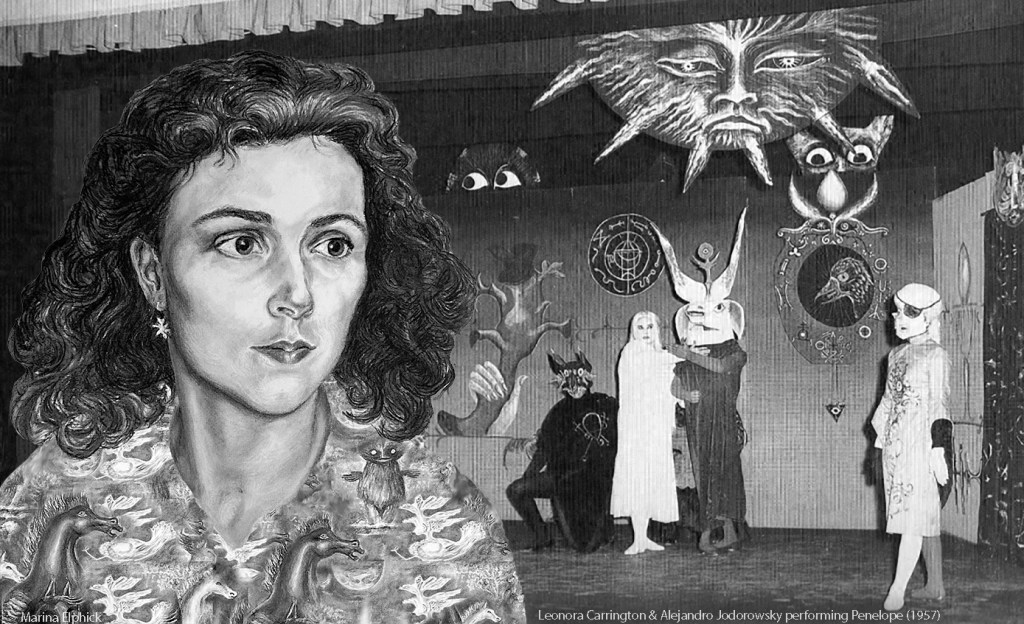

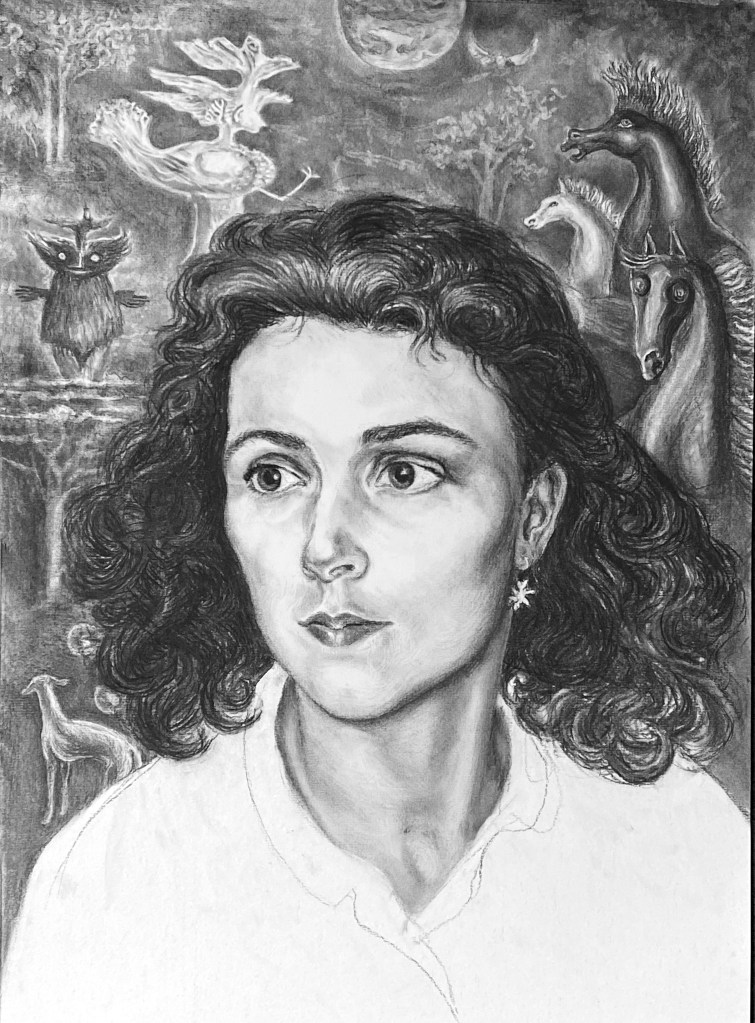

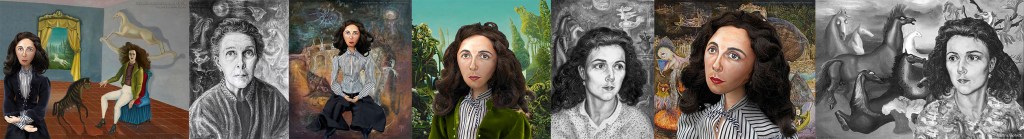

Portrait of Leonora Carrington, Charcoal on paper, by Marina Elphick.

Leonora Carrington lived an extraordinary life, filled with rebellion, creativity, and independence, breaking free from the constraints of her family, lovers, and societal expectations. From her early years as a muse in Parisian surrealist circles to her daring escape from confinement during World War II, she was determined to shape her own destiny.

In Mexico, she found both a vibrant artistic community and a place where her work could flourish, yet she consistently defied the mainstream. She rejected the role of muse, instead carving out a space for herself as an authentic artist with a unique voice that merged the surreal, the spiritual, and the personal.

As an artist, Leonora Carrington would not conform and resisted any kind of categorisation. Never settling for the easy option, she turned her back on a life of privilege and family wealth, choosing instead to flee to Paris, entering into an uncertain, yet exciting romance with the Surrealist, Max Ernst. Leonora left behind a difficult relationship with her dominant father, and the family assumption that she would live the genteel life of a debutante in fashionable society.

With Max Ernst in Paris, Leonora entered a world free of life restricted by class and gender, a place where she discovered freedom of expression in her art and her own way of painting. Yet, despite the adventure and excitement of the art movement, she was not comfortable being referred to as a Surrealist or being compartmentalised in any way.

A remarkable life story

Leonora Carrington’s early life was a complex tapestry, imbued in Irish folklore and extreme advantage yet, constrained by societal expectations and authoritarian parenting. Her defiance and artistic awakening fuelled her desire to break free and explore new realms of creativity.

Leonora Carrington was born on April 6th, 1917, in South Lancashire, England, into a world of privilege and tradition that she would later rebel against. Leonora was an artist and writer whose life and work were deeply influenced by her unusual and often tumultuous childhood. Her father Harold Wylde Carrington was a successful, wealthy, textile magnate and her mother, Maurie (née Moorhead) originated from Ireland, the daughter of a country doctor. This specific blend of English wealth and Irish heritage set the stage for Leonora’s life of artistic exploration and defiance.

Leonora muse outside ‘Crookhey Hall’, painting by Leonora Carrington,1947.

Leonora spent her early years in Crookhey Hall, a Gothic Revival mansion with sweeping views of the Irish Sea and Morecambe Bay. Grand and domineering in stature, Crookhey Hall deeply effected Leonora’s vivid imagination, she was happier in the corners and corridors of this stately home. She had three brothers, Patrick, Gerald, and Arthur, one older and two younger. The household included ten servants, a French governess, and a chauffeur, providing a ‘gilded cage’ for Leonora and her siblings. Despite these privileges, Leonora felt a profound sense of isolation and mystery in her childhood.

“Do you think anyone escapes their childhood? I don’t think we do. That kind of feeling that you have in childhood of being very mysterious. In those days you were seen and not heard, but actually we were neither seen nor heard. We had a whole area to ourselves. I think that was rather good, actually.” ( from House of Fear, BBC documentary, 1992).

Enchanted by Irish Folklore

Leonora began drawing at the age of four, an early indication of her aspiring artistic talent. Her imagination was further fuelled by the tales told by her Irish nanny and grandmother, who shared stories steeped in Irish folklore and fairy tales. This exposure to fables of ancient beings, hidden worlds, and unearthly transformations, ignited a lifelong fascination with the mystical and the magical, sowing the seeds for the fantastical imagery that would later define Leonora’s visionary artwork and writing.

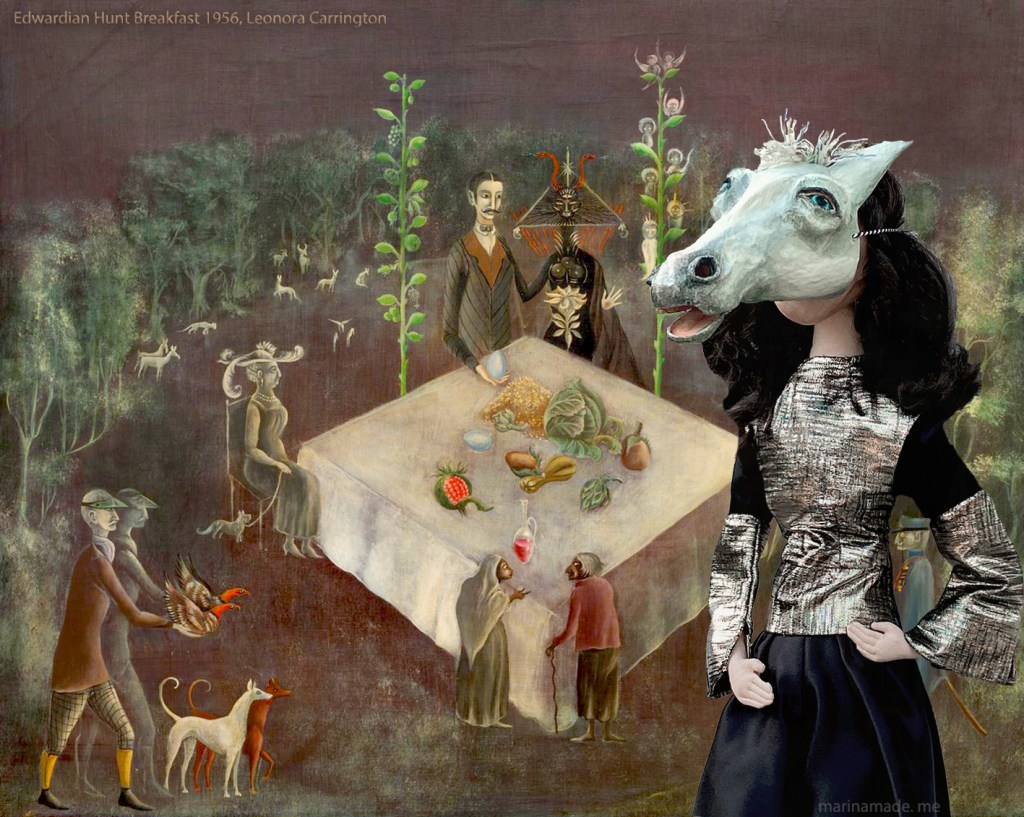

Muse with ‘The Giantess’, by Leonora Carrington, 1947. Leonora muse wearing a horse mask in, ‘The Pomps of the Subsoil’, by Leonora Carrington, 1947.

An Uneasy Education

In keeping with the customs of the time, Leonora was sent to boarding school at the age of nine. Raised in a Catholic family, she found herself in a series of convent schools, each less welcoming than the last. At the age of ten, during a visit to a Left Bank gallery in Paris in 1927, she encountered her first surrealist painting which was a revelation. Her independent spirit and unconventional behaviour led to her expulsion from two schools. Leonora’s ability to write with both hands, preferring to do so with her left hand and backwards, puzzled her teachers. The nuns labeled her as ‘mentally deficient,’ but Leonora viewed herself as simply unwilling to conform.

As she recalled:

“I think I was mainly expelled for not collaborating. I think I have a kind of allergy to collaboration and I remember I was told, ‘apparently you don’t collaborate well whether at games or work.’ That’s what they put on my report. They wanted me to conform to a life of horses and hunt balls and to be well considered by the local gentry I suppose.”

Masked muse of Leonora at, ‘The Edwardian Hunt Breakfast’, 1956, Leonora Carrington.

At a loss her family sent Leonora to a school in Florence for a year, where she attended Mrs. Penrose’s Academy of Art, and was able to discover the art of the Renaissance. After Florence Leonora was sent to a finishing school in Paris, where again she was expelled for wild behaviour.

Determined not to be sent home Leonora ran away to live with a family who she had heard about from a school friend, who accommodated her until her parents brought her back to England to prepare for her “presentation” at the court of George V at Buckingham Palace.

This was a traditional rite of passage for young women of Leonora’s social standing, a ceremonial debut into society that she found stifling and unfulfilling. Leonora described the event as resembling a cattle market. Refusing to obey societal expectations, she brought along a copy of Aldous Huxley’s ‘Eyeless in Gaza’ to read. The experience at Court, dressed to the nines and being paraded with other young women, left Leonora feeling discordant and defiant, she was adamant that she would not lead the life of a debutante.

It was after this presentation that Leonora boldly informed her family of her intention to pursue art and go to art school in London. Of course her parents were against it and her father refused to support her financially. Harold Carrington was an authoritarian of the Victorian kind, strong willed, determined and unflinching, Leonora found him unyielding and without affection. Her relationship with her mother Maurie was complex, but despite their mutual criticisms there was respect and some acceptance.

Pursuing Art Against All Odds

Undiscouraged by her parents’ opposition, Leonora was resolute in her desire to attend art school. In 1935 She left home and enrolled at Chelsea Art School in London, where she spent only a few weeks before changing to‘Ozenfant Academy of Fine Art’ in Kensington. Amédée Ozenfant was a French artist who had previously run an art school in Paris and had opened a new establishment in Warwick Road. Methodology and technique would be central to the school’s raison d’être, also an encouragement to discover for oneself the laws of art and intellectual ideas.

Leonora muse set in ‘Green Tea’, by Leonora Carrington 1947.

While at Ozenfant Leonora lived frugally in a basement flat but her determination to follow her passion for painting provided her with a sense of freedom and fulfilment, even amid financial hardship.

“From the Kings Court I went to a pigsty. I lived in a basement and didn’t have money. I barely had enough to eat but my painting and classes distracted me from this.”

Introduction to Max Ernst and the Surrealist Movement

Leonora Carrington’s life took a transformative turn on June 11, 1936, when she attended ‘The First International Surrealist Exhibition’ at the New Burlington Galleries in London. This event introduced her to Surrealist ideology and art, but it was the work of the renowned artist Max Ernst that captivated her imagination and heart.

Ozenfant Academy friends, Ursula and Erno Goldfinger arranged a dinner party to introduce the nineteen year old Leonora to Max Ernst, who was then 46 years old and an established figure in the Surrealist movement. The the chemistry between them was instantaneous and the meeting marked the beginning of a passionate relationship that would profoundly impact Leonora’s life and work. Her relationship with Max and immersion in the Surrealist movement provided her with the inspiration and freedom to develop her unique voice as an artist and writer.

When Harold Carrington discovered that his daughter had shacked up with a ‘penniless German artist, married and old enough to be her father, he was apoplectic with rage. He involved the police after discovering through his man Serge Chermayeff, that Max Ernst was showing ‘filthy’ even pornographic images at the Surrealist Exhibition in Mayfair. Harold Carrington wanted Max Ernst arrested, but news of the danger got to Max via his friend Roland Penrose and they fled to Truro, Cornwall, along with Leonora and Lee Miller.

Cornwall

The holiday cottage, belonging to Roland Penrose’s brother, made the perfect hideaway, set behind high hedges and trees. Other guests joined the house party: Paul Eluard and his wife Nusch, Eileen Agar, Gala, Man Ray and Joseph Bard. Henry Moore and his wife Irena came for lunch most days and postcards were sent to Picasso and Salvador Dali, who couldn’t be there. Historians describe it as the biggest gathering of British Surrealists on English soil.

Lee Miller took several photographs that record those three weeks in Cornwall, where rules were forgotten and defences were down.

It reflected a vision into their future, of what life could be if they left their preconceptions and expectations of others behind them. For Leonora this was a ‘golden time’, a validation of all she had ever hoped for or dared to think possible, a world beyond that of her parents.

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst at Lambe Creek, Cornwall, England, 1937.

With Max out of harms way back in Paris, Leonora went home to confront her father. She told him that she was going to Paris to live with Max and be an artist. Harold told her she was being ridiculous and the idea was preposterous, warning her she would be penniless and die without money.

Paris

Leonora did not care, at the age of twenty in 1937 she left England and headed for Paris, not eloping ( as some historians have described it) but travelling independently by boat train. She left behind her grand home, friends and family and her father who she would never meet again.

When Leonora arrived in Paris, Max took her to a bar in Monmartre where she had supper with Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dali, Andre Breton, Paul Eluard and Yves Tanguy.

Leonora found it thrilling and fascinating, she felt that she was at the centre of of something significant and pivotal. With Max at the helm Leonora was swept into the vibrant and often turbulent world of Surrealism. Leonora didn’t feel under pressure to fit in, nor constrained artistically in any way, but she never desired or needed the Surrealist label. In her later years she said she was only in the group because she was in love with Max.

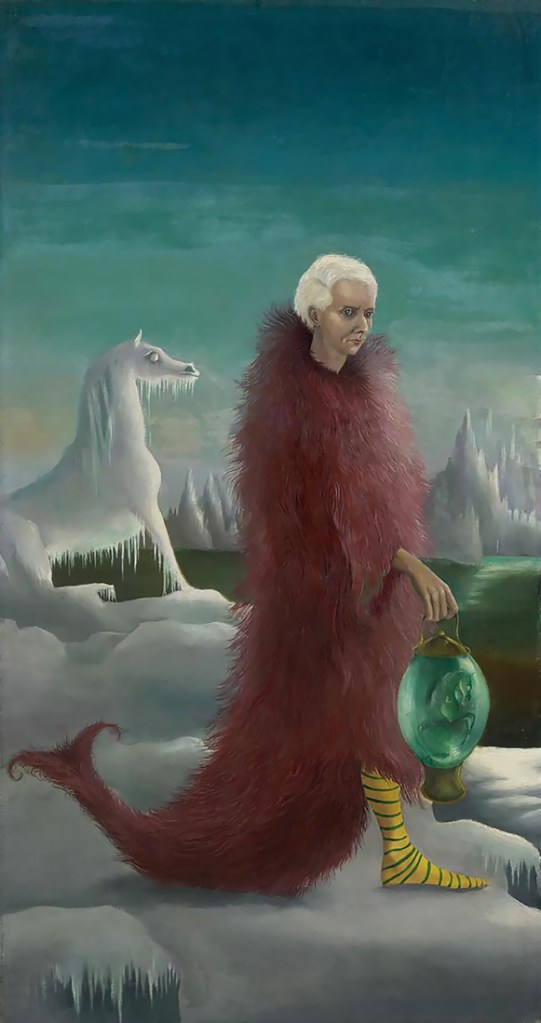

Leonora Carrington, Self Portrait, ca.1937-38.

Between 1937 and 1938, Leonora Carrington painted one of her most iconic paintings, ‘Self-Portrait’ (The Inn of the Dawn Horse). The painting shows Leonora seated in a plushly furnished chair, in a room with a window, opening to a landscape where a horse gallops in the distance. She is wearing white jodhpurs, with an outstretched hand towards a lactating hyena. Behind her, a white, tailless rocking horse hovers above her untamed hair, while Leonora’s intense gaze locks directly with the viewer, drawing them into a scene brimming with symbolism.

The recurring motif of the horse in her work, which would become central to her art, embodied her desire for freedom and autonomy.

The white horse was a personal and mythical familiar for Leonora and was linked to the Celtic goddess Epona, the goddess of fertility, whom Leonora knew well from her childhood interest in Celtic mythology, passed down by her nanny.

Muse of Leonora Carrington with, ‘Self Portrait’, (Inn of the Dawn Horse) 1937-38, Leonora Carrington.

Immersion in the Surrealist Movement

André Breton’s Surrealist circle was dominated by male artists and thinkers, who often relegated women to the role of muse rather than creator. Young women were seen as “femme infants” or “woman-children,” believed to be in direct connection with their unconscious minds and so capable of guiding male artists.

This was unsatisfactory for many women artists of the time including Leonora, who refused to be pigeonholed into this passive role. Leonora recalled a memory of Miró once asking her to get him some cigarettes, to which she replied: “Get your bloody own!”

Her confidence and defiance, traits she attributed to her privileged upbringing, enabled her to stand out as an artist in her own right. She was accepted as one of the Surrealists from the start, a testament to her talent and determination.

“Living with Max Ernst changed my life enormously because he saw things in a way I never dreamed was possible. He opened up all sorts of worlds for me.”

Leonora muse wearing a horse mask, set against, ‘The Horses of Lord Candlestick’ a painting by Leonora Carrington, 1938.

Max educated Leonora artistically, intellectually and socially, it was so much more than her convent education. Paris was an opportunity to observe and learn. No one obsessed with doing things the right way or mixing with the right people. Leonora cherished this freedom. Meanwhile Ernst made the decisive move to separate from his wife.

A year later in the spring of 1938, a Surrealism Exhibition organised by Andre Breton and Paul Eluard opened in ‘Galerie Beaux Arts’ in central Paris. Curated by Marcel Duchamp it was an exhibition that would re-write what an exhibition could be, on show was the first of what could be described as installation art, by Duchamp. It consisted of 1200 coal sacks hung from the ceiling in a room with a bed in each corner and it was about sex, life, death, desire and the subconscious.

Leonora muse wearing a horse mask, in ‘The Meal of Lord Candlestick’ 1938′, by Leonora Carrington.

Surrealism was about separating people from their expectations and compelling them to confront their deepest feelings, fears or desires.

Leonora had three paintings included in the exhibition, ‘Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), ‘The Horses of Lord Candlestick’ and ‘The Meal of Lord Candlestick’. It was a transformational moment for Leonora, she was barely twenty one and had joined the greatest names of twentieth- century art to take part in this momentous art exhibition. During this time Peggy Guggenheim, the wealthy art collector came into their lives. While visiting Max’s studio, she spotted Leonora’s painting ‘The Horses of Lord Candlestick’ and wanted to buy it for her collection Modern art.

It was also during this period that Leonora began publishing her own surrealist stories, ‘The House of Fear’ illustrated by Max, which further established her voice within the movement and acknowledged their relationship publicly.

Leonora’s mother Maurie travelled to Paris in 1938 to visit her. Although her relationship with her father had been damaged beyond repair by her affair with Max, her mother was more level headed. Maurie, concerned about the uncertain political situation in Europe, helped to support Leonora as much as she could from afar. Throughout the rest of Maurie’s life mother and daughter never lost touch.

St Martin-d’ Ardèche

At the end of Summer 1938, Ernst finally left his wife, and he and Leonora moved to St Martin-d’ Ardèche in Southern France. They found a little house on a hill just outside the village, known as ‘Les Alliberts’.

Leonora Carrington by their home near Saint-Martin-d’Ardèche

It was a ramshackle farmhouse with a terrace and beautiful views. Max had no money, but Maurie was willing to fund their new home, she wired the money from Lancashire, probably without Harold’s knowledge.

The couple were very much in love and Leonora described this chapter as, ‘a kind of paradise’. Leonora and Max immersed themselves in a creative partnership, each nurturing the other’s artistic growth.

They adorned their home with sculptures and paintings of guardian animals. Their work was integrated all over the house, with doors and kitchen cupboards painted by Leonora.

It was an inventive and experimentally resourceful time for them both and would be one of the most intensively productive periods of their lives. The artworks inside and outside made the house a ‘Surrealist’ arts haven, a masterpiece in itself.

This remote sunny corner of France that seemed far from Paris and the storm clouds of war that were gathering that summer of 1939, would not be their idyllic hideaway for long.

They had tried to keep their whereabouts secret at the start, but many of their friends came to visit them, bringing news of the political situation and the inevitable war. Max’s work had already been denounced by the Nazis, which made him a target.

The Outbreak of War

By September 1939 declaration of war had been announced. Max Ernst a refusenik and a German national, was removed and taken to a prison camp in Largentière, 50 kilometres away from their home. Leonora was devastated and her life was in turmoil, she moved to an inn near the prison so she could visit Max everyday for up to thee hours. They were grateful for this, but Leonora could not work and was lonely the rest of the time. Six weeks later Max was transferred to a larger camp in Les Milles near ‘Aix en Provence’, a former brick and tile factory, leaving Leonora isolated and unable to reach him. Distraught by the separation, Leonora devoted all her energy to try to get max released.

In December 1939, thanks to Paul Eluard’s efforts, Max was released and returned to Les Alliberts. Re-united they had some brief happiness, their deep and complex relationship found expression in mutual portraits. Max painted ‘Leonora in the Morning Light’ and Leonora painted, ‘portrait of Max Ernst’.

Leonora’s portrait revealed a sobering of her love for Max, she already sensed that remaining with Max would eventually stifle her. Although only in her early twenties, she had realised an essential truth about being a woman artist, if she remained with Max she would be dwarfed by him and hidden in his shadow. There is no doubt, Max had been her greatest tutor and inspiration, but her creativity needed to break free and develop on its own.

In May 1940 the Nazis invaded France and Max was arrested again, this time by the Gestapo due to his art being labeled ‘degenerate.’ The arrest and subsequent separation left Leonora shattered and took a toll on her mental health, a period she would later recount in her memoir ‘Down Below’.

Leonora muse with her mask in, ‘Down Below,’ by Leonora Carrington, 1940.

Leonora’s old friend from England Catherine Yarrow visited and urged her to leave France for her own safety. Leonora’s once idillic home was now very dangerous, she was desperately torn, she still loved Max and felt loyal to him, but feared the Nazis. After some thought and encouragement from her friend, Leonora decided to sell ‘Les Alliberts’ to the hotel owner for about £1000 and took Max’s passport for safe keeping, hoping to secure a visa for him in Madrid. Most of the art was part of the house and not portable, so it was left behind in the hope of Max finding it.

Mental Health Struggles

Leonora left Ardèche for the final time, with her belongings squeezed into the tiny Fiat car, alongside Catherine and her brother. The long drive south was perilous and uncomfortable in the summer heat but they pressed on until Andorra, driving day and night along roads lined with coffins and passing trucks containing bodies, with arms and legs dangling.

With the stress of travelling, grief and guilt for leaving Max, Leonora was left feeling overwhelmed and unstable; she had wild dreams which entered her daytime reality and experienced sleeplessness and vertigo.

Spain was only just emerging from the catastrophic civil war and the lacerated Spanish countryside was thick with the presence of the dead. During her time in Paris Leonora had heard many discussions about the terrible war in Spain, which the Surrealists found abhorrent and referenced in their work.

Her relief at leaving the Nazis behind in France and entering Spain was marred by confusion and her declining mental health.

They continued on driving to Barcelona, where they abandoned the car and travelled by train to Madrid. There Leonora deteriorated further, succumbing to severe anxiety and delusions which lead to her having a mental breakdown. Catherine contacted Harold Carrington and with his intervention, the family had Leonora committed to a sanatorium in Santander, a psychiatric hospital run by nuns.

Drugged and delivered there against her will, she was under the supervision of Dr. Mariano Morales, known for his brutal experimental treatment for psychotic patients.

Leonora was diagnosed as ‘marginally psychotic’ and was subjected to Dr. Morales regime of treatment with Cardiazol, a drug that induced convulsive spasms similar to electroconvulsive therapy, and Luminal a barbiturate to sedate her.

Drawing of Leonora with ‘The Horses of Lord Candlestick’, montage, based on the painting by Leonora Carrington.

Leonora was strapped to a bed by her wrists and ankles, naked and frightened and given three doses of Cardiazol over a short stretch of time, a drug regime that Dr Morales believed would restore lucidity; however the side effects included possible heart attack, jaw and spine fractures, memory loss, hallucinations and worsening fear and depression.

It was an atrocious, painful and terrifyingly dark period for Leonora, the impact of which would influence her art and writing in profound ways. In her novel, ‘Down Below’, Leonora recounted her experiences in the sanatorium describing her ‘mad’ behaviour and how she made little rituals for herself to retain a small amount of order and logic during this grim time.

There was a great irony in Leonora’s situation, the Surrealists had long been fascinated by madness and mental illness. Andre Breton argued that Surrealist works were designed to reveal the madness within normality, disturbing our understanding of sanity. Leonora showed the flip side to that in her recollections, revealing the normality within the madness, disrupting our understanding of what it is to be insane.

Leonora survived this dire yet pivotal period of her life, but not without consequences. She had been awakened to her own vulnerability and mortality, a feeling of how easily she could be destroyed.

Leonora muse wearing mask in ‘Adieu Ammenhotep’, 1960, by Leonora Carrington.

Her rescue from the asylum eventually came via a distant cousin Guillermo Gil, a doctor who was by chance working at the Santander General hospital. He visited Leonora and managed to secure a release for her on condition that she remained under the care and observation of her nurse, the formidable Frau Asegurado.

Escape

Without money or friends, only her nurse, Leonora left the sanatorium on December 31st 1940 and travelled back to Madrid. They checked into a large hotel at Harold Carrington’s expense, where they were met by a businessman friend of his, who invited Leonora to dinner. During the meal Leonora was told that her family had decided her future, she was to be admitted to a plush sanatorium in South Africa where it would all be lovely. When Leonora objected, her father’s friend offered her another solution of a pretty apartment in Madrid, where he could see her ‘very often’, as he placed his hand on her thigh!

Harold Carrington’s plan was that Leonora would sail to Cape Town via Lisbon accompanied by her nurse, however there was paper work that needed to be classified and would take weeks, so Leonora spent much time in the hotel, with occasional diversions accompanied by her nurse.

One afternoon this distraction came as a tea dance, where Leonora, who was not allowed to dance, recognised a friend of Picasso’s from Paris, who had once come to dinner with her and Max.

Renato Leduc was a Mexican poet and Diplomat and he was surprised and pleased to see her, as was she him. They spoke in French so Frau Asegurado wouldn’t understand and Leonora outlined her predicament, Renato was very willing to help. He told her he was on his way to Lisbon, then New York and she could travel with him. If she continued with her family’s plan to Lisbon and found a way to escape the nurse, they could meet at the Mexican Embassy and he would help her out of Europe.

With difficulty Leonora eventually managed to evade her nurse at a large and busy cafe. She escaped through a back exit and caught a taxi to the Embassy, already feeling a rush of freedom. She would finally be free from her father and from Hitler, although of the two she said she was more afraid of her father.

Marriage of Convenience

On the 26th May 1941 Leonora and Renato were married at the British Consulate in Lisbon, she was 24 and her husband was 43, there were no guests only two witnesses from the Embassy. They both disagreed with marriage, but it was the only way to give Leonora the diplomatic immunity she desperately needed to leave Europe and avoid further confinement.

Meanwhile Max, who had escaped from two prison camps found himself on a train to Marseille, where he met his old friend Andre Breton who was planning to leave for the USA. Soon after Peggy Guggenheim arrived in Marseille, bought some of Max’s paintings and fell in love with him. She would be Max’s passport to America, just as Renato was to Leonora.

On July 11th 1941 Leonora and Renato left Lisbon aboard S.S Exeter for their ten-day voyage to New York, on the passenger list her name was ‘Leonora Leduc’. Two days later Max and Peggy left on a Pan-Am clipper to the same destination, a more luxurious, fast and expensive means of travel.

New York

Leonora and Renato arrived in New York on the 21st of July 1941, She was finally ‘free’ and had choices. Renato found work in the Mexican Embassy and Leonora re-connected with the Surrealists many of whom were now in New York, including Salvador Dali, André Breton, André Masson, Yves Tanguy and others. Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim were now married, mainly to please Peggy and avoid the scandal of living in sin with an ‘alien’.

Max sought out Leonora and they spent pleasant days out together, which made Peggy very jealous. Max was still in love with Leonora and he was bitter that Renato, his once good friend from Paris was now married to his greatest love. However Leonora no longer felt the same about Max, they had shared history and he was good company while Renato drank in bars and clubs with his friends, but Max liked to be the centre of attention and now that he was so famous, Leonora was fully aware that she would be overshadowed by him and he would take up too much of her time.

New York began to be a productive place for Leonora, She had completed 8 paintings as well as a commission for Manka Rubinstein, sister to Helena, at $200 it was the most that she had ever sold a painting for. In art and life she was experimenting, her creative ideas were fluid and malleable, not conforming to anyone’s expectations or boundaries. From having been the quintessential ‘Femme Enfant’ of the Paris days, her worth more as artist’s muse than artist, Leonora now had gained autonomous status.

She could have effortlessly settled in an art-hungry city where, after a year she was gaining respect and invitations to exhibit, but Leonora had got used to rejecting the easy path, so when Renato made plans to return to his home in Mexico City, she decided to leave New York by her husband’s side.

Mexico

Leonora and Renato arrived in Mexico City in 1942, there had been no goodbyes to Max, in fact they never met again, that part of her life was over and a new chapter was to begin.

Mexico after the 1910-1920 revolution, in which Renato had played a part, had improved, there were new roads, schools for the poor and millions of acres of land had been redistributed to landless workers.

Mexico was now quite cosmopolitan and open to new ideas in education and business also it was opening up to North America. Mexico had an open door policy towards European refugees under the presidency of Lázaro Cardenas (1934-1940) artists and intellectuals were welcome, especially those with Spanish ancestry. They would play their part in post war Mexico and help it emerge over the following decades as a player on the world stage.

The Mexico City that Leonora entered bombarde her senses ! It was a visual feast of colour, sound and smell, an exciting city for artists and musicians, writers and scholars. People were open and friendly, yet magical and mysterious in a place of contradictions, frictions and layers of history. Indigenous people and traditions had been turned upside down by the 16th century Spanish invaders, who left a trail of fault lines never far below the surface of Mexican life.

Leonora was fascinated and entranced by this amazing new country, described by André Breton as ‘the most Surreal nation on earth’. Leonora felt at home in her new surroundings but not in her marriage. Renato who was keen to rekindle old friendships, was often out drinking with friends late into the night and left Leonora alone. This was customary as Mexican women in the 1940s did not have independent social lives, although this would start to change.

Leonora was warmly welcomed by the Mexican surrealist community, which had already established strong roots in the city. She made good friends with Remedios Varo a Spanish painter and her lover Benjamin Péret, a French poet. They lived in an old part of the city in the bohemian, ramshackle apartment on Gabino Barreda, and on the walls were original paintings and drawings by Picasso, Tanguy and Ernst, brought with them from France. As soon as Leonora entered the apartment she felt at home and Remedios became her kindred spirit and almost sister-like best friend.

In 1943 Leonora left Renato and moved in with Remedios and Benjamin. The couple held regular parties with music and discussions about art and politics, so many new friendships were made, including Kati and José Horna. For all the émigrés Mexico was a fresh start and their new home, they had left Europe bombed and scarred, their friends and families displaced or dead.

A Fresh Start

Her connections within this new circle of friends enabled Leonora to meet Imre Emerico Weisz Schwartz – or ‘Chiki” as he was nicknamed. He was six years older than Leonora, born in Budapest in 1911, he was left at an orphanage aged 4 because his mother was too poor to feed him. Chiki was steady, kind, understanding and never threatened Leonora’s sense of self or her art.

By 1946 Leonora was pregnant and she and Chiki were married. They settled in to their own apartment in the Colonia Roma, or Cuauhtémoc region of the city, originally planned as an upper-class neighbourhood in the early twentieth century but by the 1940s, it had become a middle-class quarter in slow decline.

During her pregnancy and while nursing her baby Leonora’s work was flourishing. She painted “Chiki Ton Pays” or ‘Chiki Your Country’, in which she appears to be saying, ‘this is my new world, I have my man by my side and a new landscape to explore and fresh adventures ahead’. Her life was full of promise and inspiration.

Motherhood

After an easy labour her baby boy arrived on 14th July 1946 and was named Harold Gabriel Weisz Carrington. Motherhood revealed a maternal instinct that she never knew she had and Pablo followed Gabriel 16 months later. Leonora was good at muddling through and multi-tasking, once saying to friend, poet and art collector Edward James, “I paint with the baby in one hand and the paint brush in the other”.

Leonora was living and working in a country with a vibrant art scene, but she never entirely connected to it. Her long creative life in Mexico was mostly lived out on her own artistic path and unique experiences. She had as little as possible to do with Gallery experts, art critics or art historians, she claimed to be a democratic artist, preferring to enable others rather than overwhelming or confusing them with high-brow explanations.

“Your view is as important as anyone else’s” , “ You have as much right to say what you feel about a painting as anyone has”.

Leonora ignored what the critics said about her work from the beginning, having little regard for them. Trying to gain acceptance held no attraction to her.

Muse figure with ‘Nine, nine, nine, 20th Century’, Leonora Carrington, 1948.

An artist in Mexico

1940s Mexican art was dominated by, “Los tres Grandes”, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Siqueiros. Their artistic styles were different but they were all muralists and their work was heavily influenced by the events of the revolution earlier in the century. All three were socialists interested in the history of Mexico, its indigenous people and the damage of the 16th century Spanish invaders. Diego Rivera was the most successful, in his murals he created a succinct and colourful summary of the history of Mexico, its people and the injustices they suffered. They were proud of their Mexican artistic heritage and the prehistoric art of their country, so felt no need to adapt to the European style of western art.

Frida Kahlo, artist and wife to Diego, celebrated her Mexican lineage in her work and drew from her own tragic life experiences. Through their mutual friend André Breton, Leonora visited Frida, several times at the Blue House where she lived and worked. Frida was ten years her senior and bedridden at that time, only accepting a few visitors. Leonora admired Frida’s work, which was so different to her own yet in one way very similar. Both women gleaned from their own experiences and life events and were determined to reflect life through the female perspective.

Success and friendship

In February 1948 Leonora had her first substantial exhibition at Pierres Gallery, New York, which gathered favourable reviews, including one in Time Magazine. Leonora felt that she had made some of her best work while pregnant so was delighted that the show was a triumph, however Leonora sent her good friend Edward James to represent her, not wishing to leave her baby boys.

She was finally becoming a success in her own right and no longer felt any need to be part of the mainstream Surrealist movement.

Leonora had found new excitement in her slightly run down neighbourhood in Mexico City. It had become the centre of the universe for her family and friends, all of whom lived nearby.

Their tightly knit group had at its centre, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna, who had a been through long exhausting and emotionally draining journeys to get to Mexico.

Domesticity did not limit their lives since their ‘outsider’ status as Europeans, meant they were not bound by the traditional rules ascribed to women in macho Mexican society. As labour came cheap in Mexico even poor artists could afford a maid.

Her friendship with Remidios in particular, became one of the most precious of her life, together they fused their strength and imagination and enjoyed the exchange of ideas. This often lead to similar themes being explored in their work, but Leonora rarely collaborated with other artists.

Leonora and her group of friends had made a radical departure from an art movement started in Paris, by men who viewed women simply as their muses. Leonora had rejected the role of muse early on, saying, “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse… I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.”

Leonora with her mask, seated with, ‘The Old Maids’, Leonora Carrington, 1947.

Leonora, Remedios and Kati found their own surrealism and took it to a new area, it was woman focussed, intuitive and visionary.

The house in Colonia Roma which had hosted many meetings of the Surrealist friends gave Leonora what she had always been searching for, a safe base from which she could work and thrive as an artist, and a home to bring up her boys.

Shocking Events

In 1968 two of Leonora’s best friends died, Remedios Varo and José Horna, both deaths hit Leonora hard, but the loss of Remedios felt like losing a sister, they had been seeing each other almost every day for twenty years, supporting and inspiring one another. Mexican poet Octavio Paz, described the friends as; ‘a pair of beautiful Surrealists who shared the same inner vision for living and creating work in a kind of vacuum untouched by worldly ambition, wealth or social constraint’.

Also in 1968 the Tlatelolco massacre happened, where 300 peaceful student protesters were shot dead in Tlatelolco plaza during the lead up to the Summer Olympics. The Mexican government reported it as lawful suppression of a violent riot, however they had placed 360 government snipers on rooftops around the square, as well as troops and tanks. Millions of dollars had been spent on the Olympics, but Tlatelolco was a poor, run down area and the people were unhappy.

Leonora was horrified, both Gabriel and Pablo were students at the university. Afterwards there were meetings attended by ordinary people to discuss possible next moves against a government who was deaf to their anguish. Leonora who was not political, attended one of these forums. There were pro Government spies and one of these denounced Leonora to the authorities as a political agitator, so Leonora decided to leave the country to avoid arrest.

Back to America

Leonora spent most of the next two decades in America, stopping for the first month in New Orleans and then New York and finally Chicago. Now in her early fifties she was still hungry for new life experiences and was not afraid to be alone in a strange city, having to make new friends. For Leonora it was an opportunity to discover unexplored esoteric interests like alchemy and Tibetan Buddhism, as well as Women’s Liberation, which was then in its heyday.

Leonora muse set in ‘Grandma Moorhead’s Aromatic Kitchen’, by Leonora Carrington, 1975.

Leonora and her new friend Gloria Orenstein, feminist and writer, attended rallies together and met another renowned feminist writer, Betty Friedan (‘Feminine Mystique’). Leonora was aware that her own existence in Mexico had been unburdened by misogyny, but women in the country around her were frequently oppressed.

In 1972 Leonora designed a poster for the Mexican Women’s Liberation movement, “Mujeres Conciencia” ( Women of Conscience). On her visits to Mexico she wanted to share her new ideas with friends and build an interest amongst ordinary Mexican women.

Love

Leonora lived in poverty in New York, she remained married to Chiki, but had love affairs. She believed her romantic attachments were her own business and had nothing to do with anyone else. She believed in love, but not in marriage break up at any price.

Leonora and Chiki were fond of and respectful of one another, nonetheless Leonora would not allow herself to be ‘shackled’ by the conventions of marriage. She was not a proponent of free love, but valued her relationships with intellectuals, one was a Nobel prize winner and another, a playwright who she worked with designing props and costumes.

Return to Mexico City

Finally it was Chiki with his deteriorating health that lured Leonora back to her home in Mexico City. They were both getting older and she needed somewhere more permanent to live in the last years of her life, rather than the series of bedsits she had been living in, in America.

On the 19th September 1985 Leonora experienced one of the most frightening and shocking events of her life. The ground beneath her feet began to shake violently, it was a massive earthquake with a magnitude of 8.0 which devastated the city and killed at least five thousand people. The area where Leonora lived was severely affected, but thankfully her own house was undamaged.

Old Age

Leonora was not afraid of aging, to her it was an equal part in the adventure of life. She intended to continue making challenging choices, as long as she had the ability to choose.

Having been a beautiful young woman, it was a blessing to cast off her ‘femme-fatal’ role. Her love affairs had sometimes inspired her, but over time they contained and consumed her; they could be complicated and demanding as well as a responsibility. Leonora mesmerised men well into her 60s.

Leonora flourished in her old age, she positively revelled in the visual elements of later life, playing with taboos and exploring new ideas in her novel, ‘The Hearing Trumpet’. Her wild and unpredictable landscapes were as interesting and surreal as the work of her earlier years, the sculptures she made in her garage appeared like thee dimensional versions of the creatures that inhabited her paintings, uniquely captivating. Being an old lady didn’t blunt her edge, Leonora remained as sharp as a hawk.

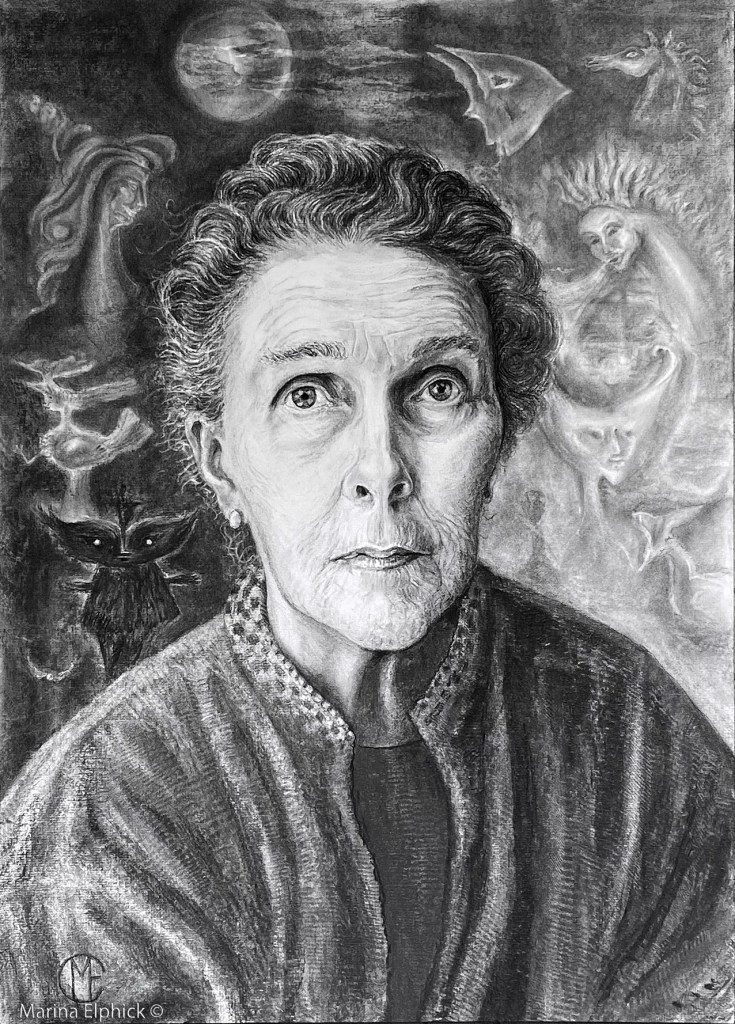

Portrait of the mystical Leonora Carrington, charcoal on paper, Marina Elphick.

In 2007 Chiki died at the age of 96, he had been unwell for many years, yet it was a bigger shock to Leonora than she had anticipated. He was one of the last of her generation, as she had lost her old friend Kati Horna in 2000.

In 2006 just before the death of Chiki, Leonora was reunited with a member of her British family, Joanna Moorhead, a second cousin, who discovered her fabulous relative by chance. Over the next five years Joanna visited Leonora twice a year, travelling to Mexico City, where she would hear stories of Leonora’s incredible life and would share and exchange family stories of those Leonora had left behind. This new relationship, although late in her life would have given Leonora a source of comfort and reconciliation, a chance to reflect on her long creative time as an artist.

In her final years Leonora became almost invisible in the art world, a kind of mythical status grew around her; The eccentric English lady artist who lived the solitary life of a recluse and was nervous of strangers.

In May 2011 Leonora became ill with pneumonia and was admitted to hospital. Her rebellion and tenacity were no longer any use however hard she struggled, she died on the 25th of May with her sons by her side.

Throughout her long and evolving career, Carrington rejected conventional success, preferring to follow her own path, which was deeply personal and connected to her own vision. Her work embodied her deep curiosity about the world, esoteric knowledge, and the strength of the female experience, all of which informed her painting, writing, and even her feminist activism later in life. She embraced motherhood, remained unafraid of aging, and continued to create until her final years, becoming a symbol of resilience and artistic integrity.

Leonora Carrington left behind a legacy not just as an artist but as a woman who refused to be defined by others, continually reinventing herself and her work.

Leonora muse in front of a version of, ‘les distractions de dagobert’, by Leonora Carrington, 1945.

Earlier this year, Carrington became the highest selling British-born female artist at auction when her painting, ‘Les Distractions de Dagobert’ (1945), sold for just over £22.5 million at Sotheby’s in New York.

Leonora Carrington muse seated with white horse mask and Portrait of Leonora Carrington, charcoal, by Marina Elphick.

Bibliography and Acknowledgements

Leonora in The Morning Light by Michaela Carter, Simon & Schuster 2021

Leonora Carrington by Joanna Moorhead, Virago 2017

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington, Dorothy, publishing Project 2017

The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington, read by sian Phillips, Naxos AudioBooks 2017

Muse of Leonora, set in the morning light’. By Max Ernst

Please feel free to comment, I’m always interested in people’s thoughts

Thank you 🙏 Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person