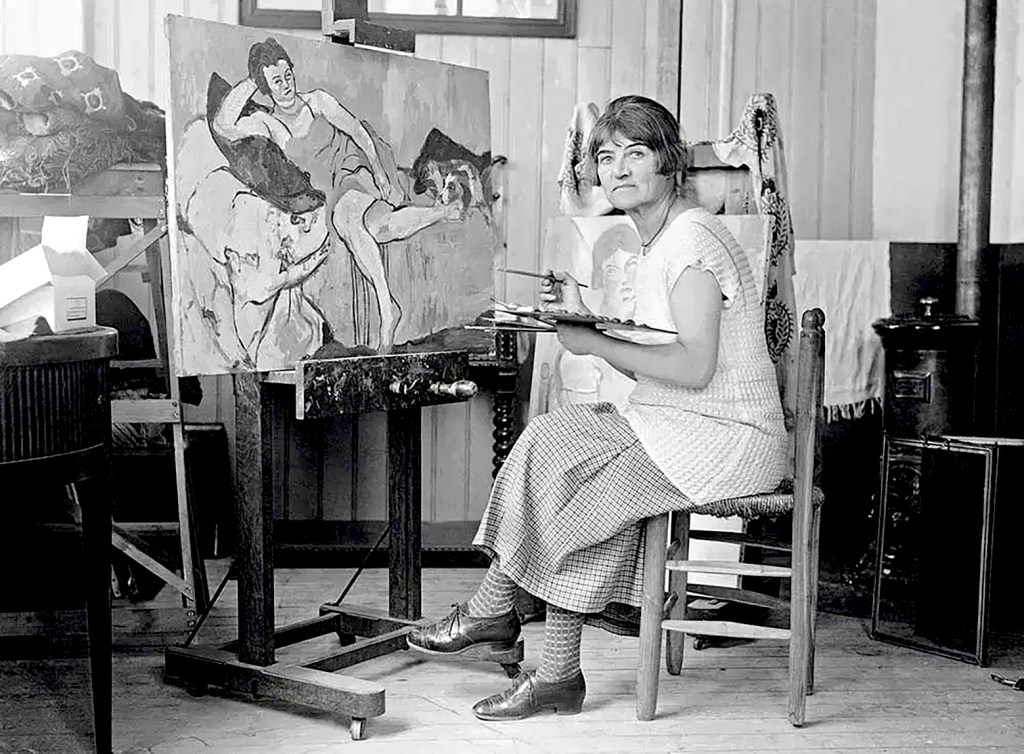

Suzanne Valadon was a woman who lived as vividly as she painted.

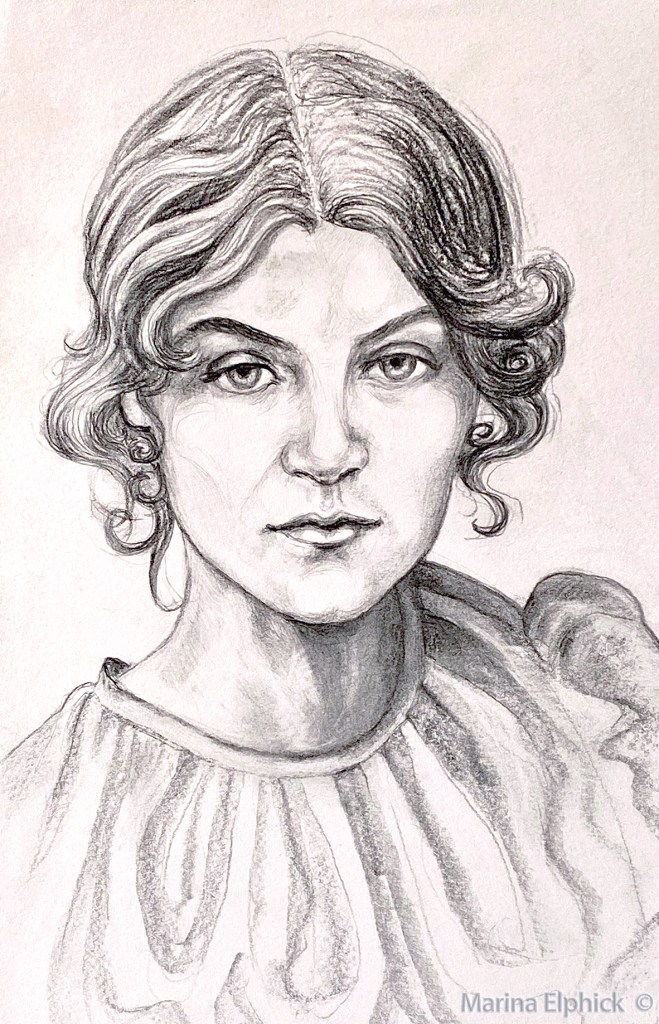

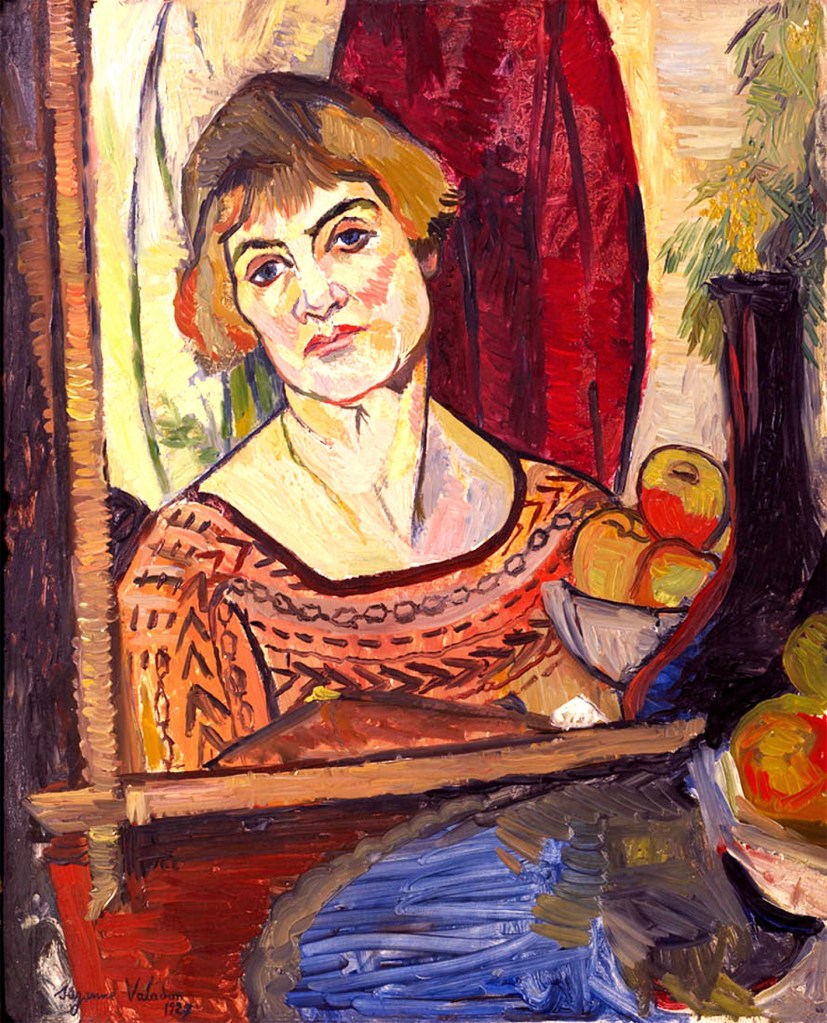

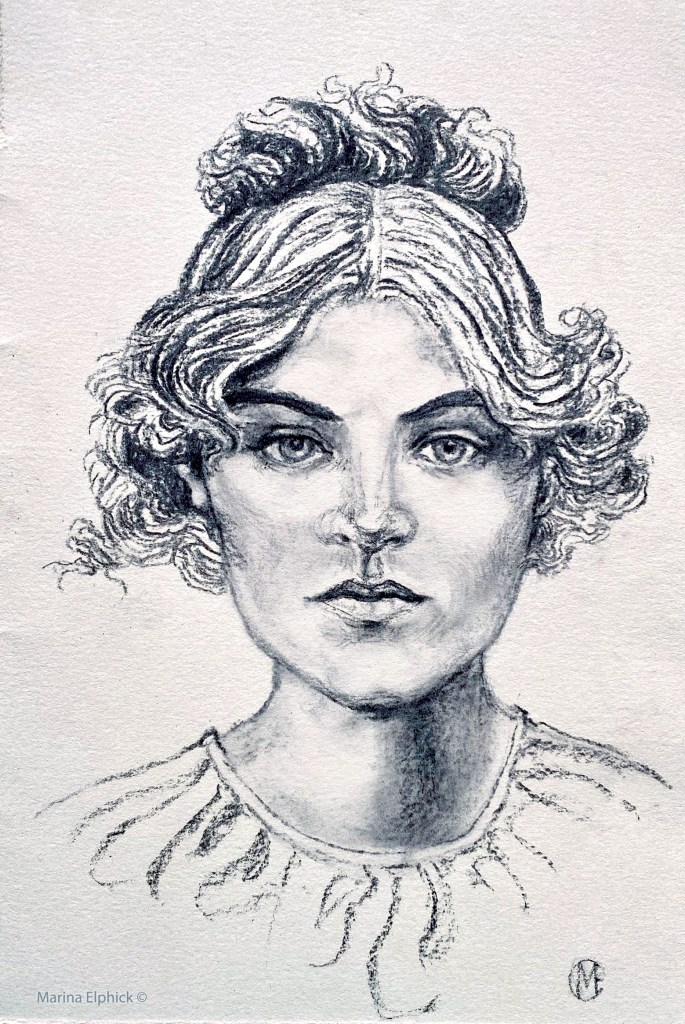

Suzanne Valadon, pencil, by Marina Elphick, 2025. Self-portrait, 1927, by Suzanne Valadon.

Early life

Born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in 1865, she entered the world already marked by hardship.

Her mother, Madeleine, was a laundress from the rural village of Bessines near Limoges. Unmarried and wanting two escape local prejudice, Madeleine moved to Paris with hopes of a better life. She was seduced by the sight of the windmills on the hill of Montmartre and chose to live there, only to be disappointed by poverty and loneliness.

Windmills at Montmartre, early 1900s, unknown photographer.

Madeleine raised her daughter single-handedly in cramped lodgings at the foot of Montmartre. She had hoped to find work as a seamstress, as she had good references, but work was scarce and she had to settle for the menial job of a cleaning and scrubbing woman, for her landlady. Alcohol dulled Madeleine’s despair, and her daughter grew up largely without stability or tenderness.

Drawing of a young Suzanne, by Marina Elphick. Madeleine Valadon with her daughter Suzanne, c.1880

The young Marie-Clémentine Valadon, later known as Suzanne, imagined in Montmartre in the late 1800’s.

Her education was fractured and short lived. Marie-Clémentine (Suzanne) attended a convent school run by the Sisters of St Vincent de Paul, but lessons were disrupted by the Franco-Prussian War and the bloody uprising of the Paris Commune.

The convent closed its doors, leaving her to roam freely in the streets of Montmartre, which became both her playground and her classroom. Its cobbled lanes, windmills, circus acts, jugglers, and dancers ignited her imagination far more than any textbook could.

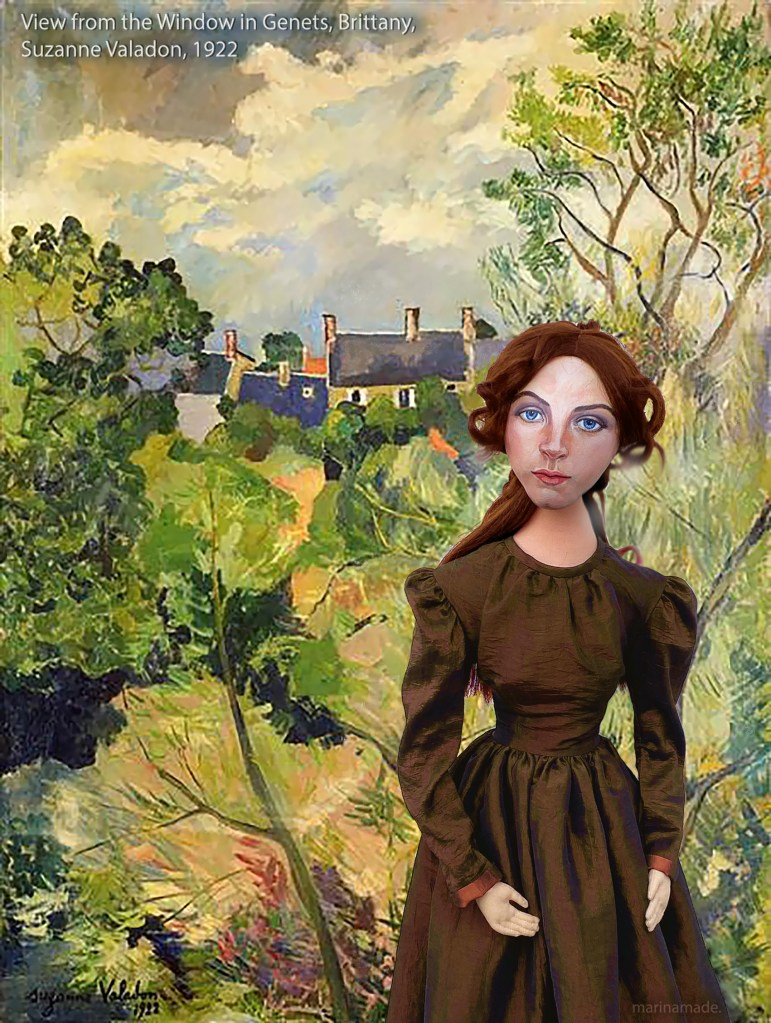

Suzanne Valadon imagined by The Three Windmills in Montmartre, in a painting by Maurice Utrillo in 1922.

Suzanne muse with,’ View from the Rue Cortot’, painting by Suzanne Valadon. Muse with The Violin Case, 1923, painting by Suzanne Valadon.

Fierce, small in stature, and quick to anger, she earned the nickname “the Little Valadon Terror”, from neighbours. The absence of formal schooling was both a loss and a gift: it pushed her to teach herself, she started drawing and painting aged nine, cultivating resilience and resourcefulness that would later shape her artistic voice.

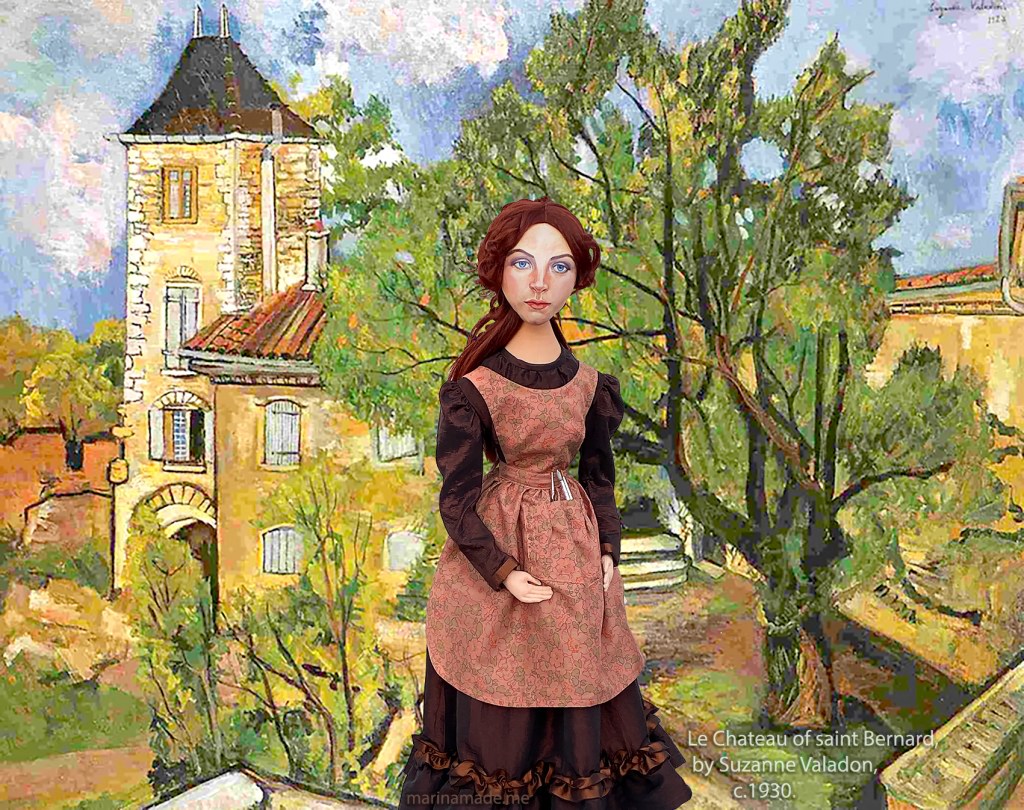

Muse of Suzanne by Marina at ‘Le Chateau of saint Bernard’, by Suzanne Valadon, 1930.

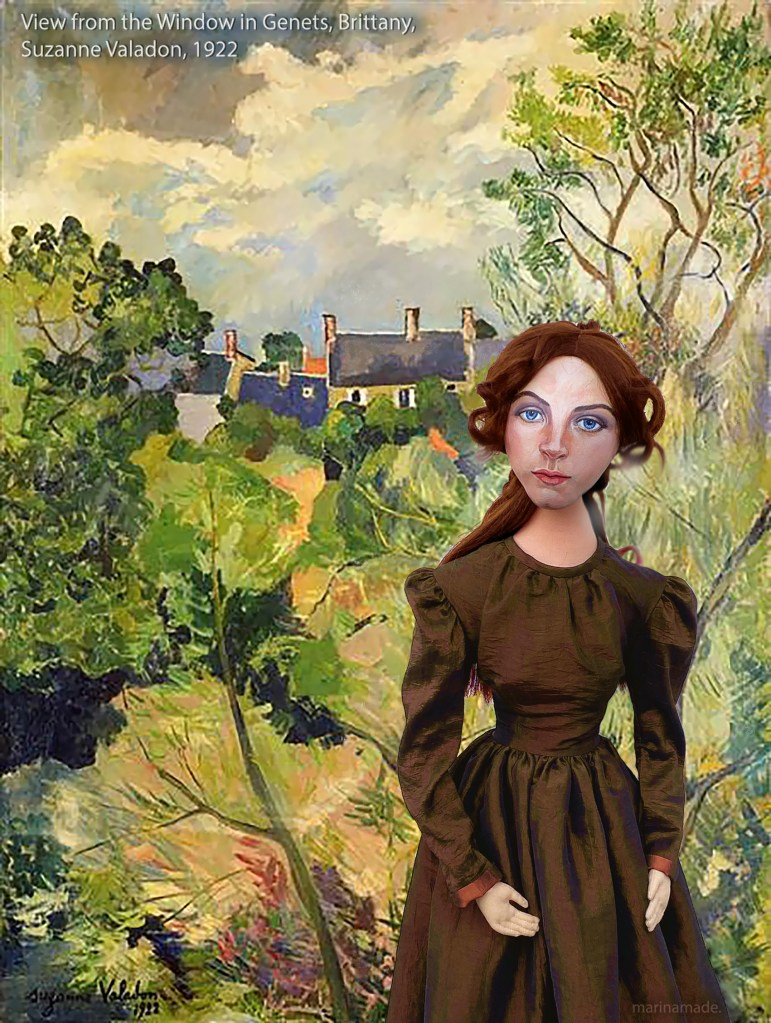

Muse with,’View from The Window in Genets ‘, painting by Suzanne Valadon. Charcoal Sketch of Suzanne Valadon, Marina Elphick.

From an early age, she defied convention: she tumbled through a world of acrobats and circus acts, performing with a fearless grace that earned her admiration and attention. Aged fifteen, restless and unwilling to accept the narrow roles open to working-class girls, she joined the circus as an acrobat.

For a time, she soared above the crowd, tasting freedom in the physicality of performance. A fall ended this dream, but it revealed a pattern that would last a lifetime: when one path closed, she forged another. She did not retreat into despair; she reinvented herself as Maria, a name chosen to help her fit in with the young girls from the outskirts of Naples who had settled in Paris

The Acrobat, or Wheel, Suzanne Valadon, 1916. Marie Clementine (Suzanne) Valadon, The Circus 1889.

L. Early self Portrait, by Suzanne Valadon, 1883. R. Suzanne Self Portrait, 1898.

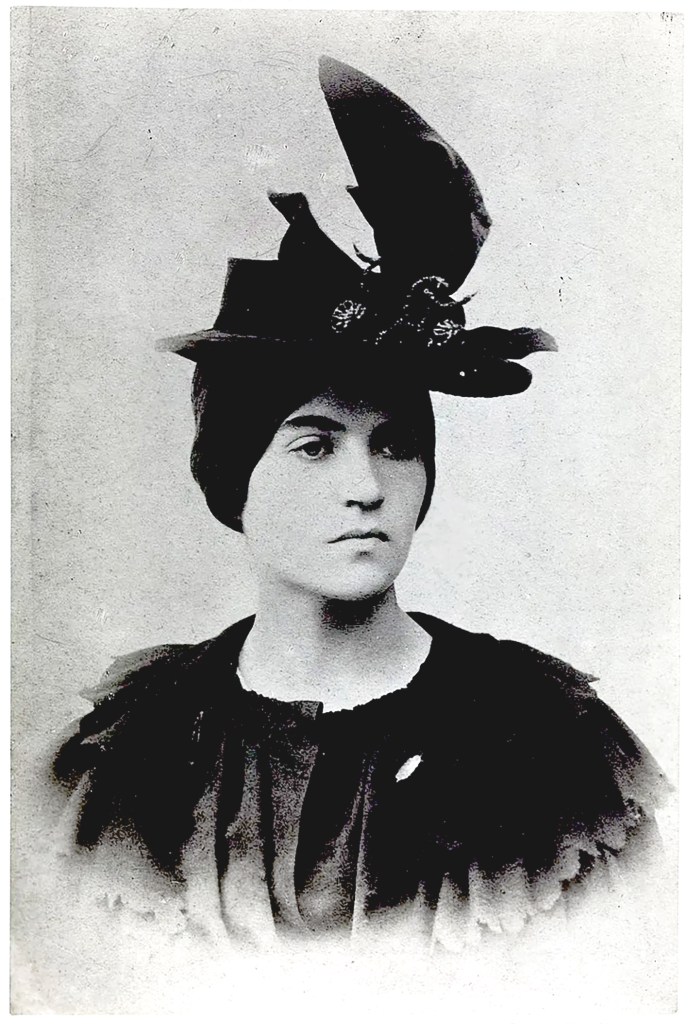

Suzanne Valadon Photographs c. 1985, she was then known as Maria.

The next reinvention came in the studios of Montmartre’s artists. With her striking looks and magnetic presence, she quickly found work as a model. Montmartre, in those years, was a universe unto itself. Cafés and cabarets, like the Chat Noir and the Auberge du Clou, were the pulse of the city, frequented by painters, poets, musicians and performers.

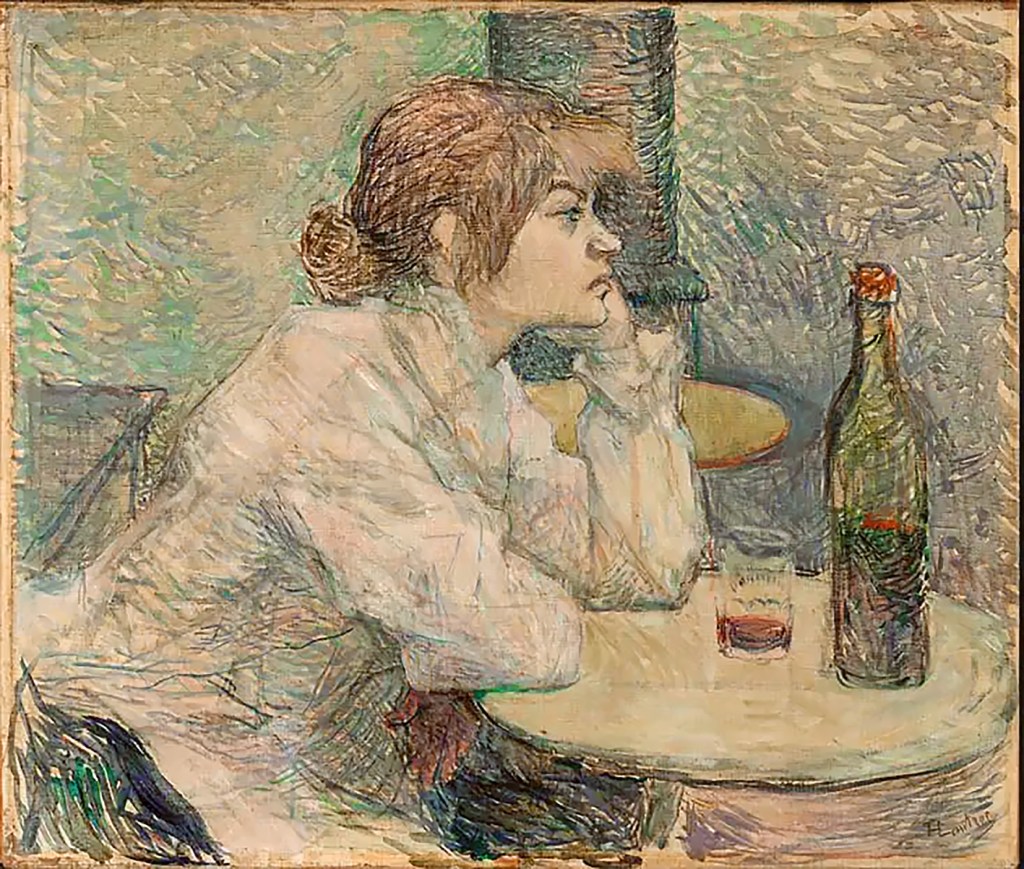

The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, c. 1887-1889

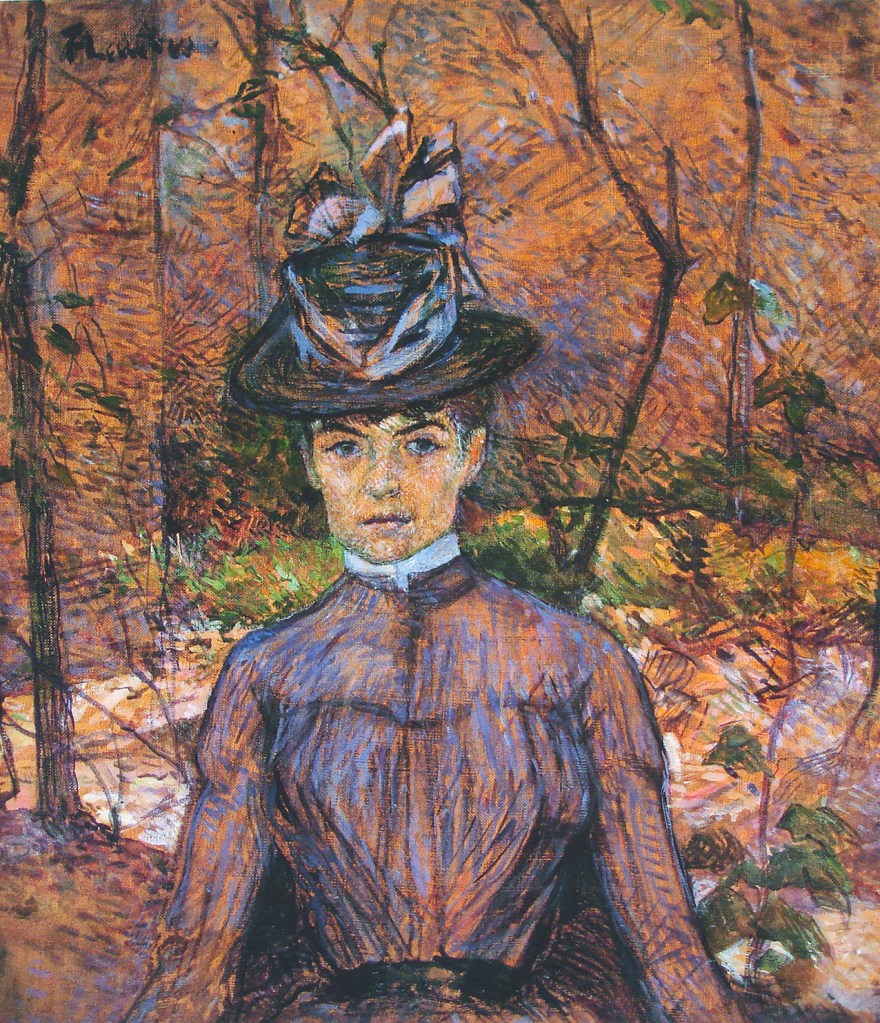

Two Portraits of Suzanne Valadon, both painted by Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, 1885.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec admired Maria’s vitality and independent spirit. It was he who suggested Maria change her name to Suzanne (an allusion to the Biblical story of the chaste Susanna who repels the advances of two old men). Lautrec sketched her with an intimacy that captured both strength and sensuality, seeing in her a muse who embodied the very essence of Montmartre’s bohemian charm. Lautrec not only painted her but encouraged her ambitions to draw and paint herself.

Pierre-Puvis de Chavannes, The Sacred Wood Cherished by the Arts and the Muses, 1884-1889. Suzanne Valadon was used a the model for all the figures in this painting.

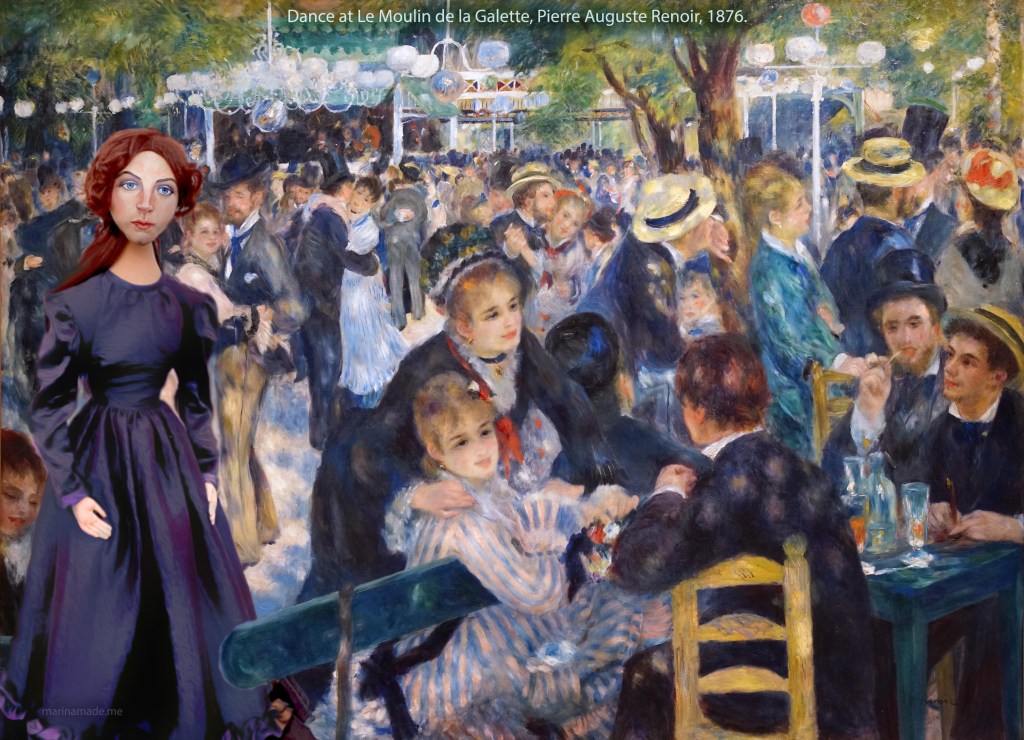

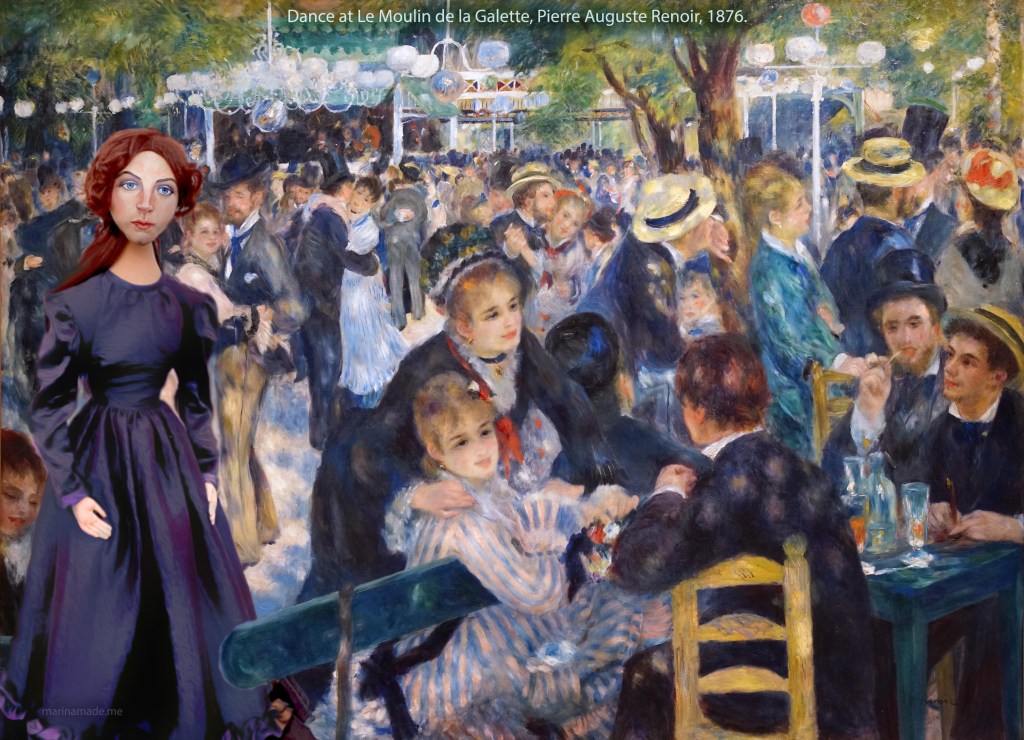

Other artists she modelled for and was inspired by include Puvis de Chavannes, whose measured, classical gestures informed her compositional sensibility; and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who captured her youthful vitality in works such as Dance at Bougival and whose luminous palette influenced her handling of colour, light, and the human form.

Suzanne muse imagined at the ‘Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette,’ Renoir, 1876.

Suzanne Valadon may have been insouciant and light-hearted about her lovers, but she was serious about her intention to become an artist. Modelling paid little, but it offered Suzanne something far more valuable: an apprenticeship by observation. Day after day, she surreptitiously studied the artists’ techniques during her long hours of posing, sketching obsessively in private.

When Toulouse-Lautrec discovered her drawings, he was so struck that he pinned them to his wall and dared visitors to guess their creator.

Nu à la toilette, by Suzanne Valadon, 1892

When Toulouse-Lautrec introduced Suzanne to Edgar Degas, he became her greatest champion. On the very day they met, Degas purchased one of her chalk drawings, a symbolic gesture of faith that transformed Suzanne’s confidence. Degas was exacting, but he admired her determination and treated her as a peer.

Degas offered her rigorous guidance, encouraging her to study anatomy and composition, laying the technical foundation that would underpin her future masterpieces. She became a fixture at his home at 37 rue Victor-Massé, where she called each afternoon, absorbing not only his artistic discipline but also his belief in her talent.

Two Figures (After the Bath, Neither White nor Black), 1909, by Suzanne Valadon.

Degas arranged for her work to be promoted by two of Paris’s most influential dealers, Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard. It was Vollard who gave Valadon her first solo show. And when Degas suggested that she exhibit at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1894, she became the first woman ever admitted, an achievement so unprecedented that it caused a stir in Paris.

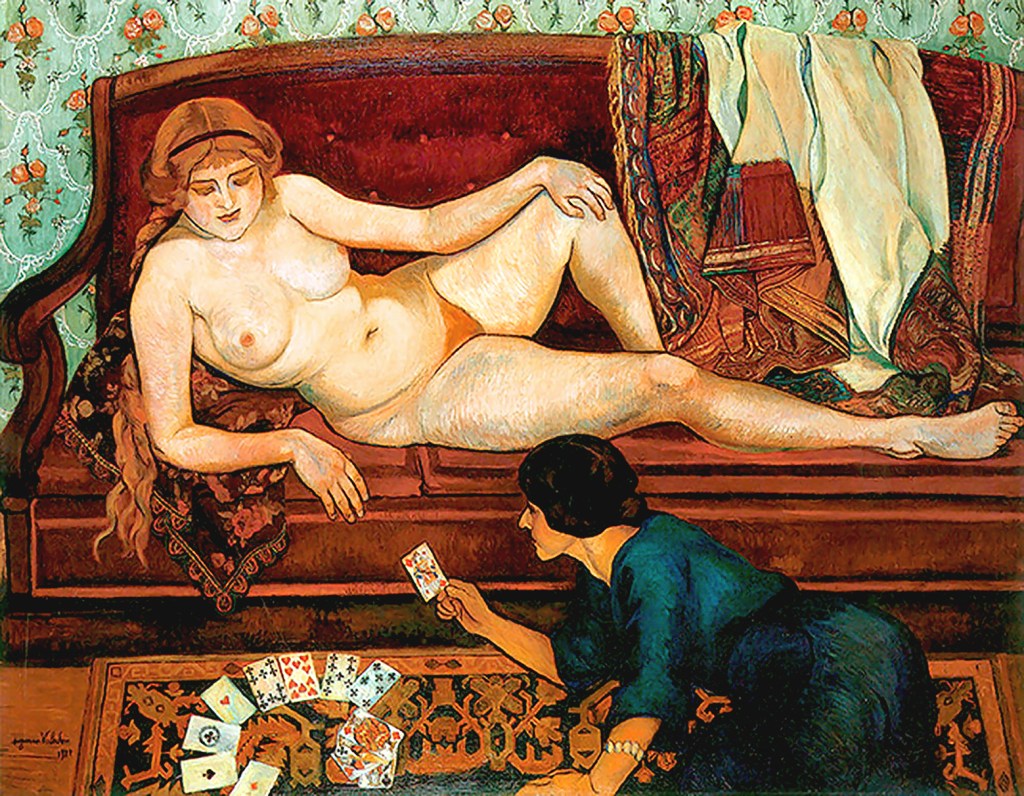

Suzanne Valadon, The Future Unveiled, 1912, oil on canvas.

Suzanne Valadon the Painter

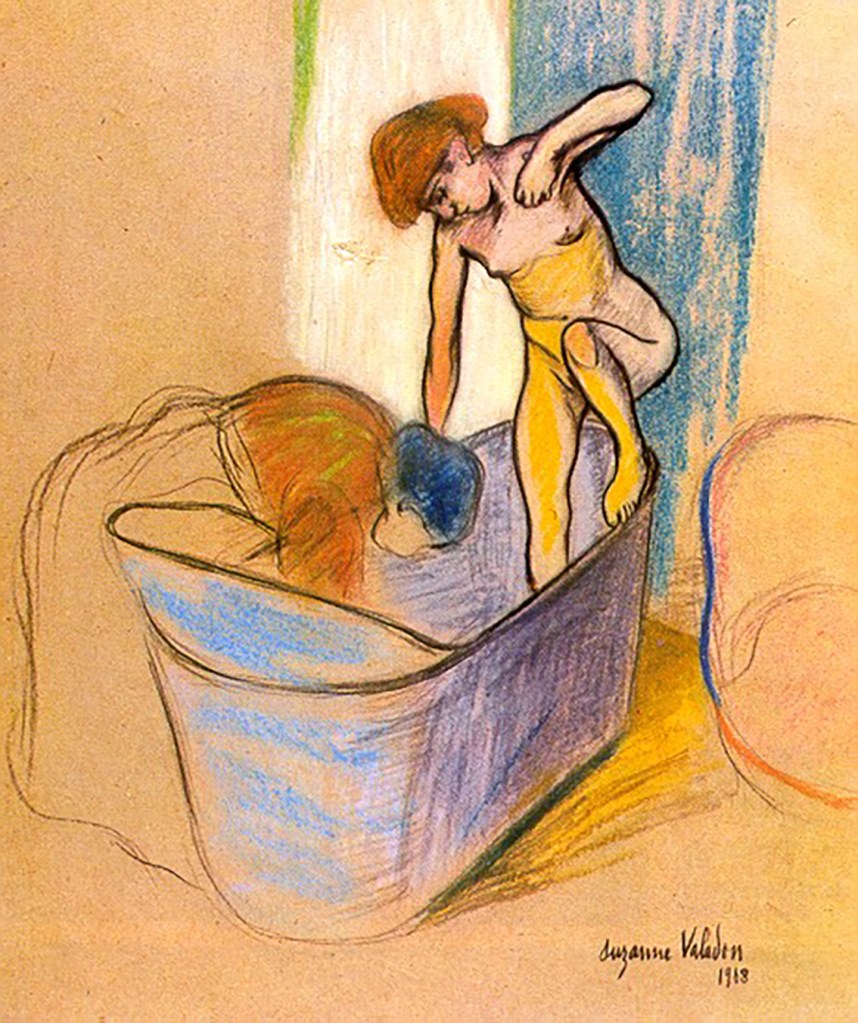

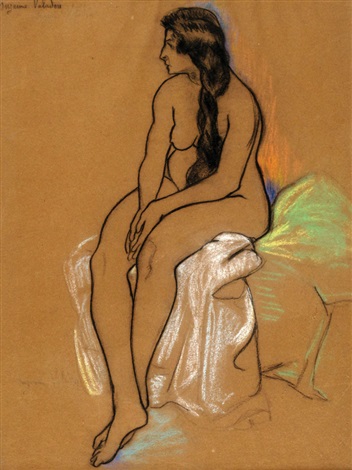

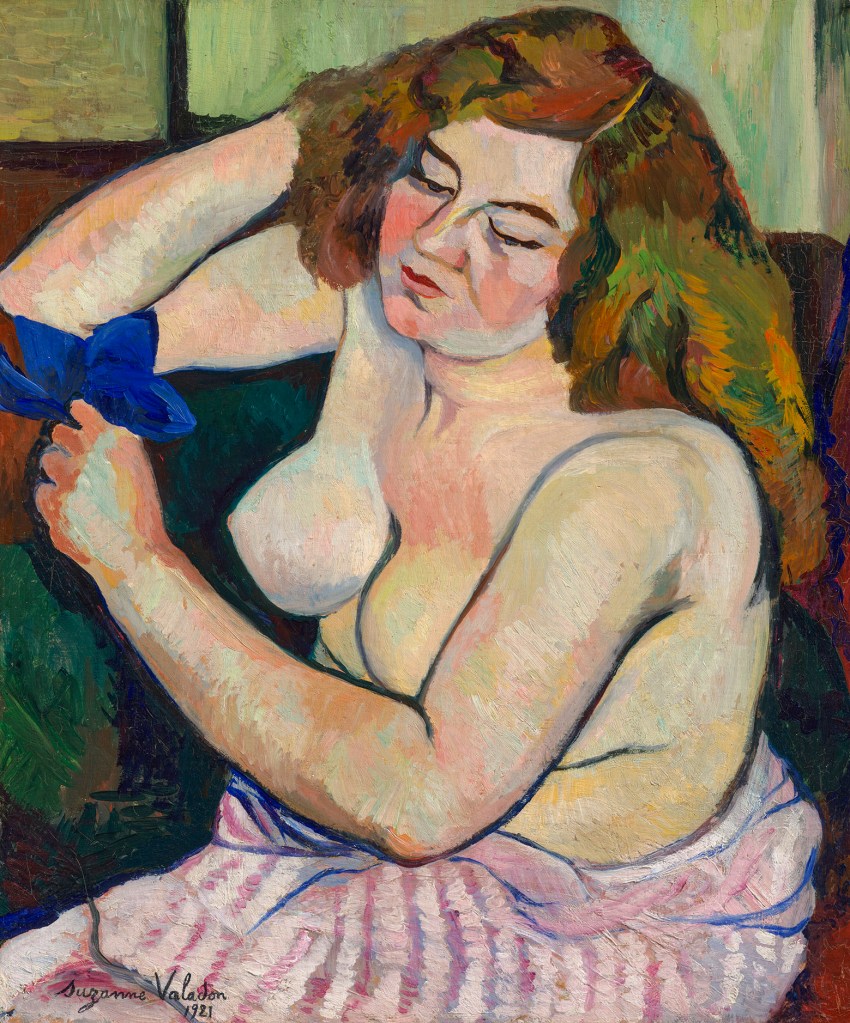

By the late 1880s, Suzanne was producing her own paintings, drawings, and etchings. Her subjects were the people around her: women washing, children playing, intimate portraits of family and lovers.

Where Renoir had idealised her body in soft hues, Suzanne depicted women with unflinching honesty. Flesh in her paintings was solid, textured, and alive; bodies owned rather than objectified. In a world where women were so often the painted subject but rarely the painter, Suzanne’s gaze was radical.

Nude with drapery, Suzanne Valadon, 1921. Nude combing her hair, by Valadon ,1916.

While contemporaries such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, who were born into wealth and were sheltered from Parisian street life, moving within rarefied circles, Valadon had an entrée into cafés, cabarets, and the smoky heart of Montmartre. Those doors, forever locked to her well-heeled female peers, were wide open to Suzanne. She thrived in this atmosphere, uniting her lived experience with her artistic eye.

Montmartre remained her greatest muse. She wandered its streets, sketching the energy of performers at the Moulin Rouge, the vibrancy of café life, and the everyday resilience of its working-class inhabitants. By then, Montmartre was a tumult of creativity and contradiction: dazzling entertainments for the crowds, while garrets brimmed with impoverished painters scraping by on absinthe and bread. Suzanne, no stranger to hardship, thrived in its contradictions.

Her personal life was as unconventional as her art. She had relationships with artists including Puvis de Chavannes and Renoir, and later lived with the composer Erik Satie, who was besotted with her. Satie described her as the great love of his life, though she left him after a year, breaking his heart. These affairs often overshadowed her art in the gossip of her time, yet they reflect the intensity with which she lived, refusing to bow to convention or respectability.

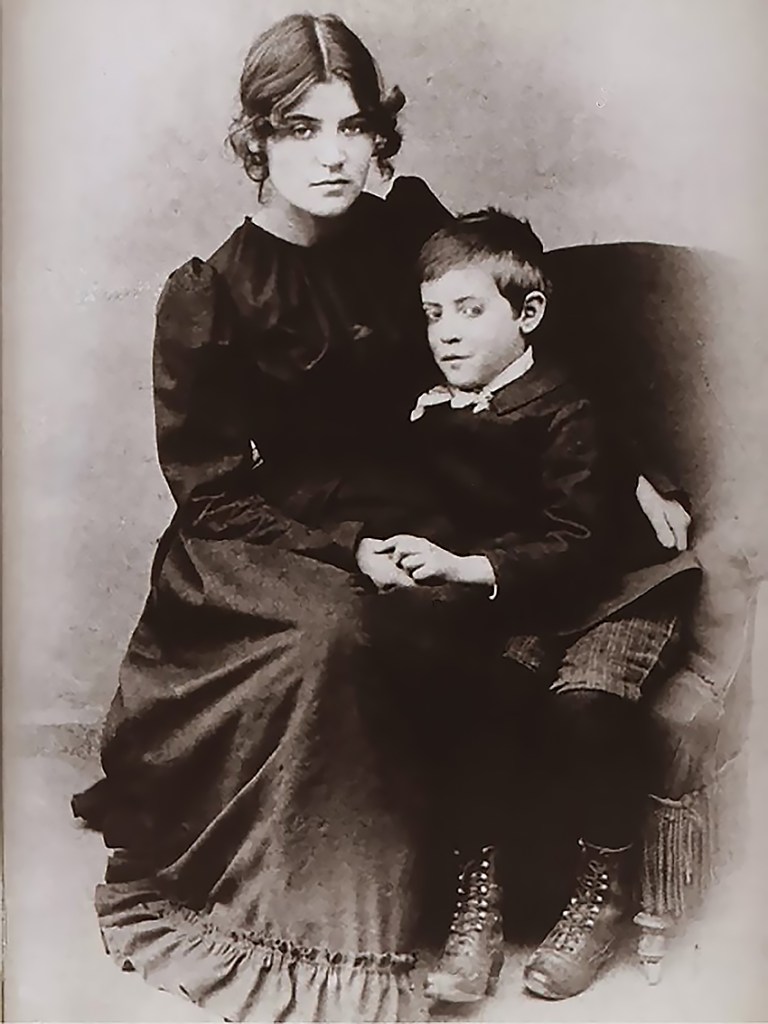

Detail of nineteen year old Suzanne Valadon with her baby son, Maurice Utrillo, 1884. Photographer unknown.

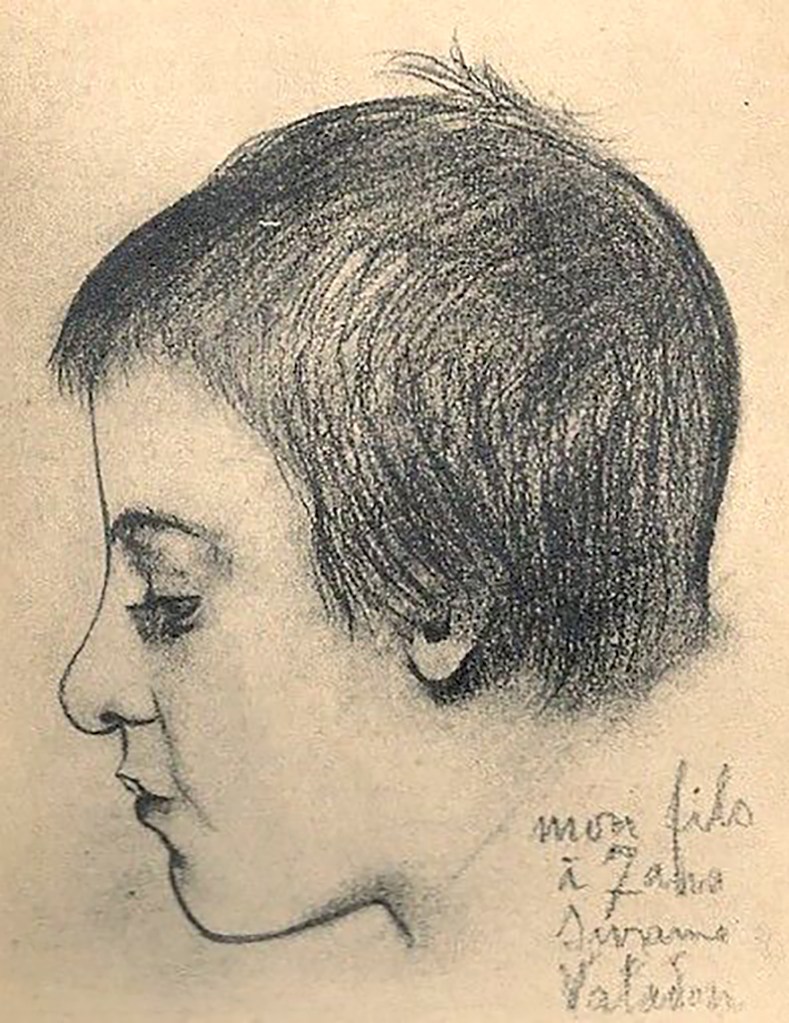

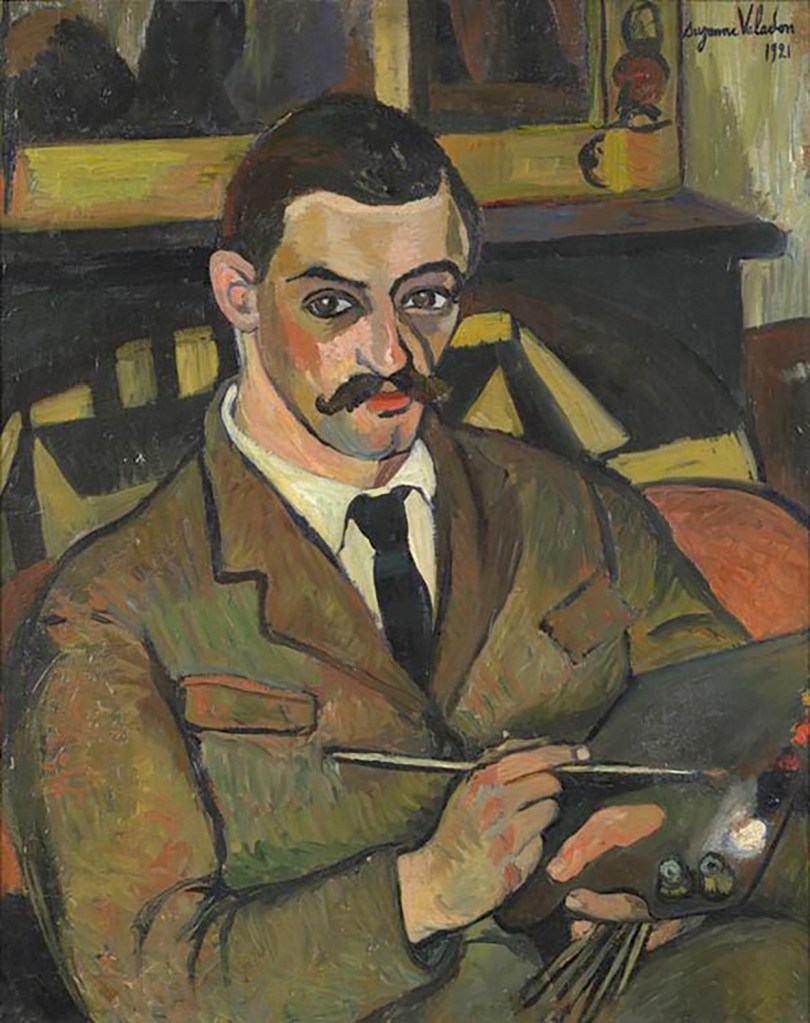

At eighteen, Suzanne gave birth to her only child, Maurice Utrillo in 1883. She raised him largely alone, with intermittent support from her mother, while she pursued her art. Maurice inherited her talent and her instability. He would become a celebrated painter of Montmartre street scenes, though alcoholism and mental illness shadowed his life. Suzanne painted him often, with tenderness tinged by anxiety.

Utrillo at 7 years old, Drawing on paper, by Suzanne Valadon, 1890.

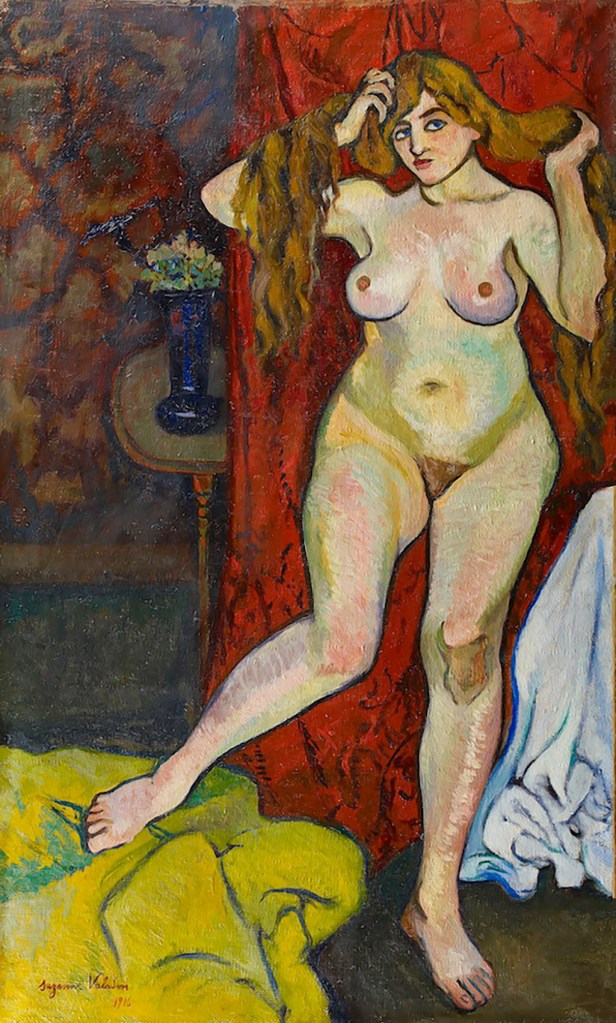

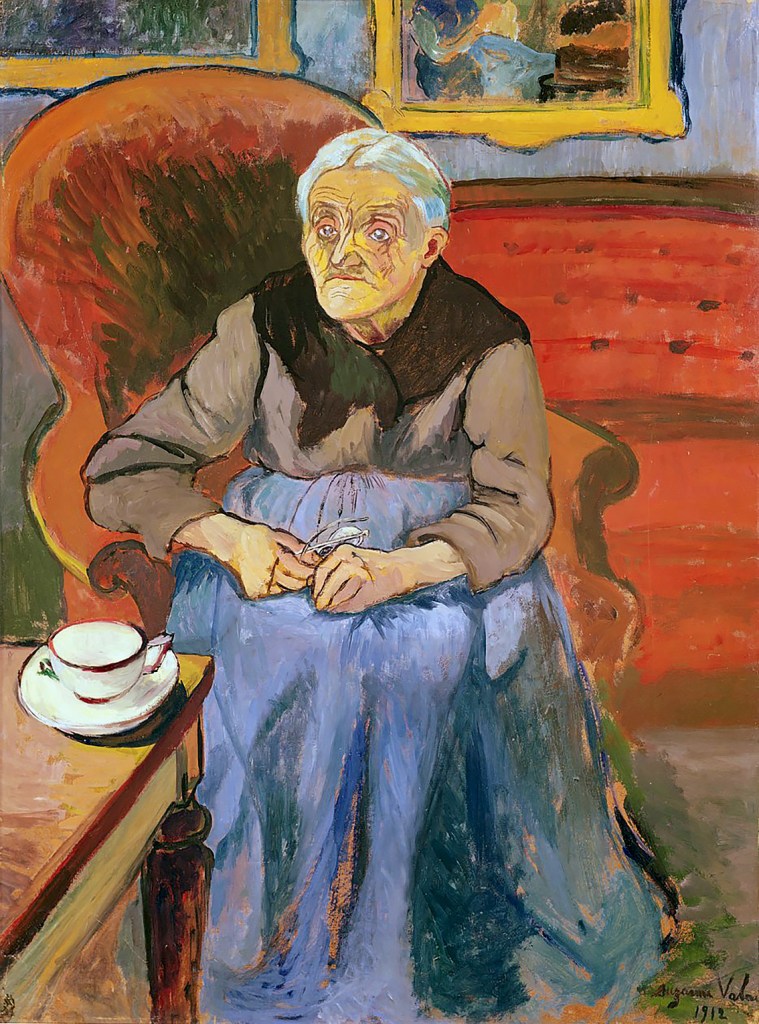

By the turn of the century, Suzanne had carved out her reputation. She was no longer a model who sketched on the side, but a recognised painter whose work was exhibited internationally. Her paintings, ‘The Bath (or Two nudes)’ 1923, and ‘Nude sitting on a sofa, 1916’, portrayed women as self-possessed, active, and dignified.

She painted her mother, wrinkled and weary, with as much gravity as her nudes. For Suzanne, beauty lay not in perfection but in truth.

Nude sitting on a sofa, 1916, by Suzanne Valadon. Portrait of the artist’s Mother, Valadon, 1912.

The Bath (or Two nudes) by Suzanne Valadon, 1923.

In 1895, Suzanne married the stockbroker Paul Mousis. For thirteen years she lived with him in relative stability, dividing her time between an apartment in Paris and a house in the countryside. Yet domestic security could not contain her restless spirit.

Pastel portrait of Suzanne Valadon, imagined in her years of success, by Marina Elphick

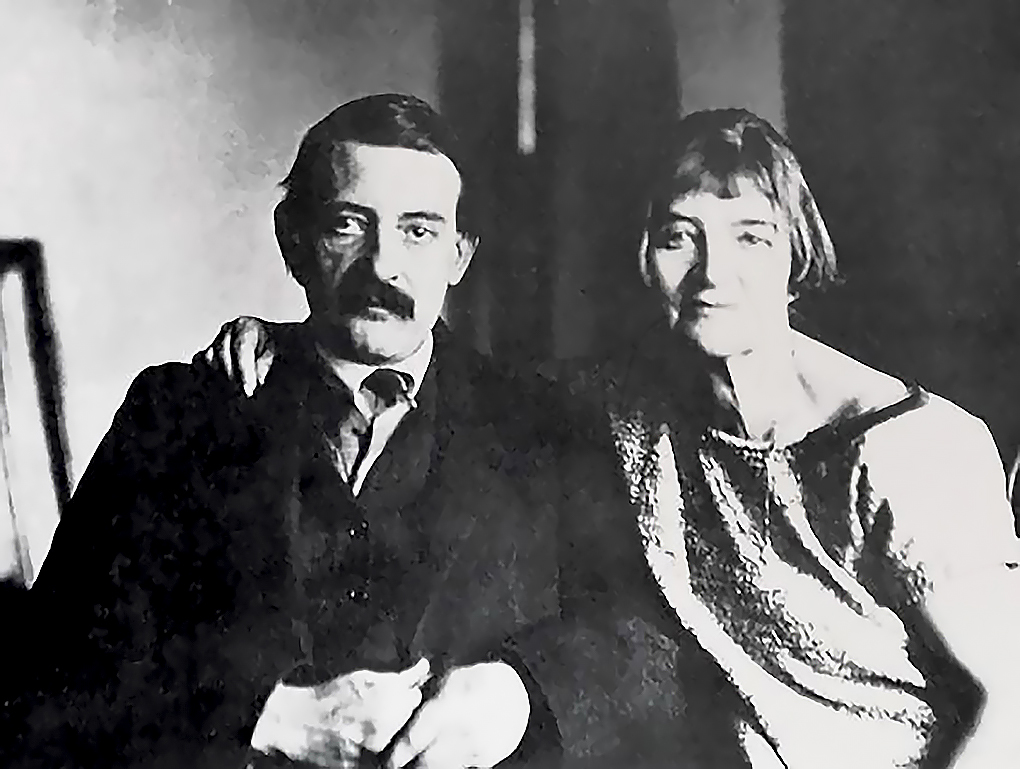

In 1909, she began an affair with André Utter, a painter twenty-three years her junior and a close friend of her son. He became her model and appears as Adam in Adam et Ève, painted that same year. She divorced Mousis in 1913.

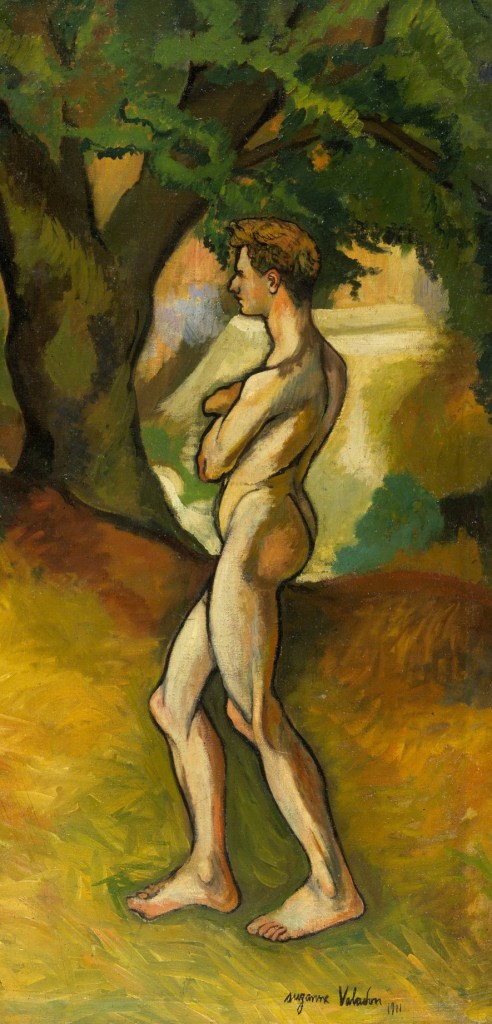

Adam and Eve, by Suzanne Valadon, 1909) oil on canvas. Suzanne and Andre Utter were the models for this painting. Suzanne Valadon, Joy of Life, 1911, Andre Utter.

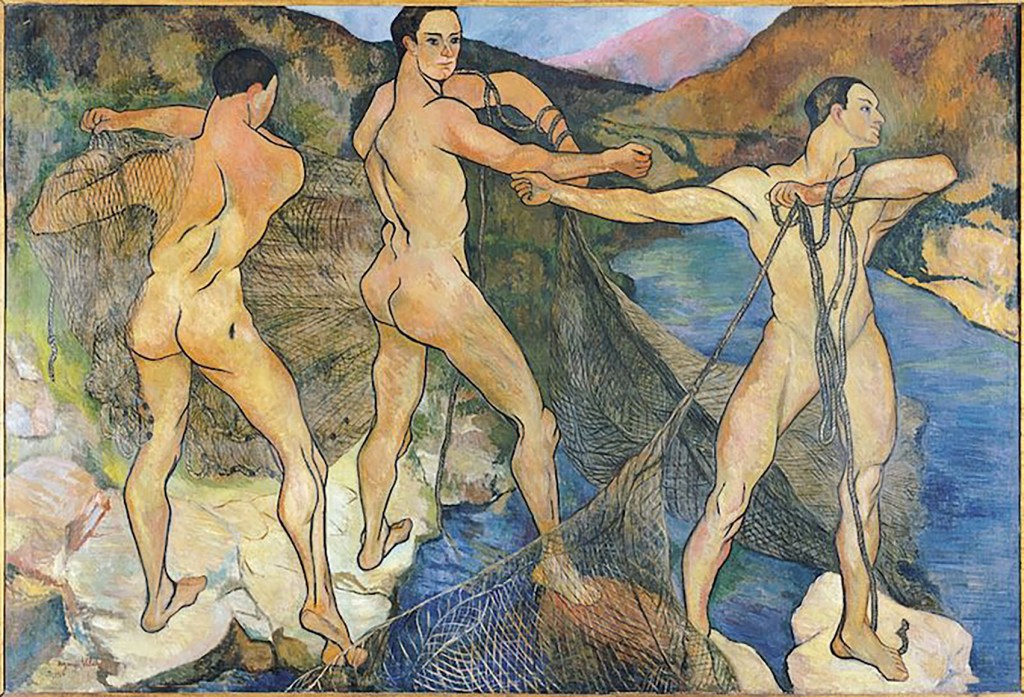

Casting the Net, 1914, by Suzanne Valadon.

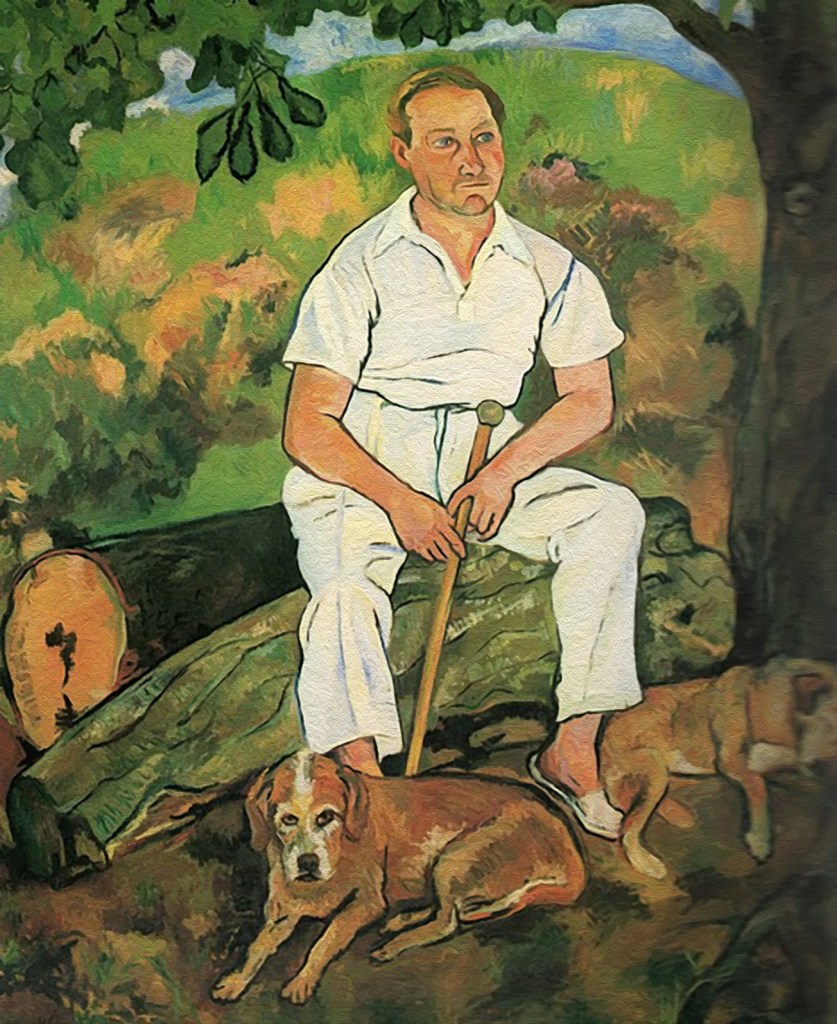

In 1914, nearing fifty, she scandalised Paris by marrying André Utter. Their stormy relationship became the subject of gossip, but Suzanne remained unapologetic. She painted André often, reversing the tradition of the male gaze. Her canvases, like her choices, were declarations of freedom.

The interwar years brought both triumph and difficulty. Her works were shown abroad, and her name was etched among France’s most formidable painters. At the same time, she shouldered the burdens of her son’s illness and her household’s volatility. Yet she painted with vigour into her sixties, her work radiating the same fearlessness that defined her youth.

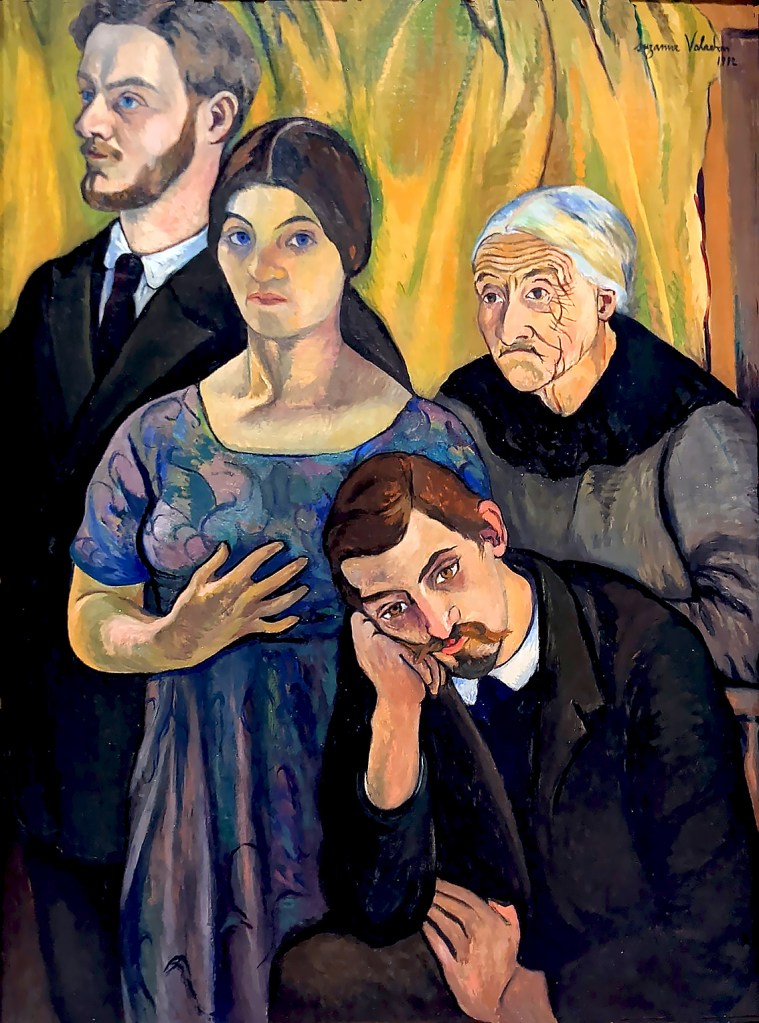

Suzanne Valadon Self Portrait with Family. André Utter, Madeleine Valadon and Maurice Utrillo, 1912.

In 1915, Suzanne’s mother died, her son Maurice was placed in an asylum, and her husband was fighting in the First World War. Her art persevered despite these personal crises.

In 1917, the Bernheim Jeune Gallery staged a joint exhibition of works by Suzanne, Maurice, and André. Though sales were initially modest, notable collectors like fashion designer Paul Poiret purchased works, sparking a surge of interest among Parisian art dealers.

After the war, Suzanne’s reputation solidified. Her works were sought by collectors, her exhibitions acclaimed, and in 1920 she was elected an associate of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. She became increasingly assertive, demanding admiration from Utter and asserting her importance as an artist.

Charcoal drawing of Suzanne Valadon, 2026, by Marina Elphick

While her household could be fraught with arguments and personal crises, she was also a generous benefactor to Montmartre, reputedly tossing 100-franc notes to street urchins from her rue Cortot window.

She cared deeply for her family, commissioning a granite tomb for her mother and inscribing it with: Valadon, Utter, Utrillo.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Suzanne continued to paint and exhibit prolifically. She hosted gatherings for young artists, mentored emerging talents, and maintained a luxurious yet eccentric lifestyle at her château near the River Saône.

She navigated her son Maurice’s fame and fragility with care, employing a nurse and guiding him through periods of mental instability while supporting his artistic achievements. Her friendship with Gazi, a devoted young artist, provided companionship and assistance in her later years.

Andre Utter and his dogs, 1932, by Suzanne Valadon. Maurice Utrillo, by Suzanne Valadon , 1921.

Suzanne’s legacy was cemented through her exhibitions and the critical acclaim of her peers. In 1937, she participated in the Women Painters Exhibition at the Petit Palais alongside Vigée Le Brun, Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalès, and Sonia Turk, reflecting on her own humility in the presence of such talent while still claiming her place as France’s greatest woman painter.

Bouquet in blue Vase, Suzanne Valadon, 1932. Portrait of Genevieve Camax-Zoegger, 1936, by Suzanne Valadon.

Nature Morte, 1922, by Suzanne Valadon. Raminou Sitting on a rug, Suzanne Valadon, 1920.

Vase of Flowers on a Chair, 1927. Still Life with Flowers and Fruit, Suzanne Valadon, 1932.

Suzanne Valadon died in 1938 at the age of seventy-two, after a stroke while painting a floral still life. Her funeral gathered artists, including Picasso, Braque, and Derain, as well as writers who knew her worth, recognising her place in Montmartre’s story and in the broader history of art.

Today, she is remembered not merely as Renoir’s model, nor only as the mother of Utrillo, but as a pioneering painter celebrated for her honesty, vitality, and audacious vision, who dared to depict women as they were: strong, flawed, sensual, and human. Mentored by the likes of Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Puvis de Chavannes, and Degas, she transformed observation into creation, absorbing lessons from her teachers and the vibrant city around her.

Montmartre may have been the stage of her youth, but through her work, Suzanne Valadon made it immortal; a canvas of courage, vitality, and the resolute spirit of a woman who refused to be confined.

She was laid to rest at the Cimetière Parisien de St Ouen, her life a testament to resilience, creativity, and the power of female agency in a world often dominated by men.

Legacy

Suzanne Valadon left behind over 450 paintings, 300 drawings, and 30 etchings and perhaps more importantly, an example of what it means to seize authorship of one’s own image. She began as an outcast child, feral in Montmartre’s streets, then as a muse to others. But she ended as a painter of fierce independence, refusing to flatter, refusing to idealise. She painted women not for men, but for themselves and for the truth of the world she had known.

She remains a reminder that art need not be polite, that beauty can emerge from defiance, that a woman need not be muse alone. Suzanne Valadon was always, at heart, Montmartre’s little “she-devil,” as she was nicknamed in childhood, mischievous, unyielding, and burning with life until the very end.

Catherine, lying on a panther skin, by Suzanne Valadon, 1923.

Acknowledgements and References

https://www.artbasel.com/stories/suzanne-valadon-centre-pompidou-19th-century-women-artist?lang=en

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/valadon-suzanne

DailyArt Magazinehttps://www.dailyartmagazine.com › suzanne-valadon

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel, Nancy Ireson, Published by Paul Holberton Publishing Ltd, 2022

My Muse of Suzanne Valadon

My art muse doll of Suzanne Valadon represents her as a very young woman. Incredibly her artistic interests and creative life started early, she was self taught and took herself out to the streets of Montmartre, where she sketched people who lived around her. By the time she modelled for the renowned artists, she was already quite accomplished at drawing and painting.

Fascinating, thank you so much for sharing. Best wishes Brigitte

>

LikeLike

thank you so much for the most precious , sparkling and meticulate description of Suzanne Valadon. You made her come to life and managed to make her work even more inspiring.

Your essays are a joy to read: lively, enthousiastic and well documented. The muses have become dear to me and are received with great joy.

Thank you again from The Netherlands,

Marjolijn Bos

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you that is so nice to hear!

LikeLike

Fantastic Marina. Informative and beautifully written. Your pencil drawings are amazing and your muse another winner to add to the collection. Well done.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great 👍

LikeLiked by 1 person