Bella

Many of Marc Chagall’s most regarded and famous paintings feature Bella, his wife and muse, who inspired his life’s work and fuelled their love story.

My muse of Bella Chagall was contemplated a long time before I created her. The work was influenced by the dream-like quality of Marc Chagall’s numerous paintings of her, often as his bride, which are permeated with his love for her. These paintings inspired my portrayal of Bella, I saw her as Chagall’s ethereal, loving, fantasy bride with green hair, wearing a floaty dress and veil. My muse is not meant to be a realistic likeness of Bella, but more of an impression of her and their love for one another.

Meeting Chagall

It was mutually love at first sight and pure coincidence when the couple first met in the summer of 1909. They where visiting friends in St. Petersburg and found that they had a similar way of seeing the world, forming an instant attraction between them.

Marc (or Moishe as he was then known) was twenty-two and Bella was fourteen. The intensity of that first encounter was to remain with them, keeping them spiritually close even when apart.

Bella Rosenfeld

Young Bella Rosenfeld was born in 1895 to wealthy jeweller Shmuel Rosenfeld and his wife Alta Leviente, who were Hasidic Jews and ran a successful business in Vitebsk, Belarus.

Bella was the youngest daughter and she had eight older brothers and sisters. In the Russian Empire at that time, Jewish children were not allowed to attend regular Russian schools or universities, but money must have made a difference, because Bella attended a Russian language school in Vitebsk and went on to attend the University of Moscow. There she studied history, philosophy, and literature and became an accomplished writer, supplementing her studies by writing articles for a local Moscow newspaper.

By the time that the fateful meeting occurred between Bella Rosenfeld and Marc Chagall in 1909, Bella was a well educated, studious girl and talented young writer; Marc, the son of a poor Jewish fishmonger, was an art student studying painting under Yehuda Pen and about to be apprenticed to Léon Bakst, the revolutionary stage designer and artist.

Love

Having fallen deeply in love they were both very enthusiastic about each other; in her memoirs Bella described Marc’s mesmerising eyes:

“When you did catch a glimpse of his eyes, they were as blue as if they’d fallen straight out of the sky. They were strange eyes … long, almond-shaped … and each seemed to sail along by itself, like a little boat…I was surprised at his eyes, they were so blue as the sky … I’m lowering my eyes. Nobody is saying anything. We both feel our hearts beating.”

Marc wrote equally poetically about Bella in his autobiography, ‘My Life’:

“Her silence is mine, her eyes mine. It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my future, as if she can see right through me; as if she has always watched over me, somewhere next to me, though I saw her for the very first time. I knew this is she, my wife. Her pale colouring, her eyes. How big and round and black they are! They are my eyes, my soul.”

The long Engagement

Her parents were not thrilled at the match, but Bella and Chagall were in love and inevitably they became engaged. Initially their relationship had to be a long distant one as they were both creative, ambitious people and had their own plans.

Bella studied her other love of acting with Stanislavski in Moscow, while Marc Chagall moved to Paris in August 1910 to develop his work.

There he discovered emerging new styles of art ; Fauvism, Cubism and Surrealism and his new friends included Picasso, Delaunay, Leger and Modigliani.

Chagall in Paris 1910-1914

The first days and weeks were difficult especially for 23 year old Chagall, he was alone in the big city and unable to speak French. Some days he “felt like fleeing back to Russia”, he so missed Bella and his family. He would daydream of them and the riches of Russian folklore, while he painted in his studio.

Chagall was constantly reminded of his home in Vitebsk, as Paris was home to many painters, writers, poets, composers, dancers, and other émigrés from the Russian Empire. He painted day and night, only going to bed for a few hours, resisting the many temptations of the big city at night.

He would not contemplate any woman other than Bella, who he adored. He began to worry about losing her, so he decided to send her a marriage proposal by post.

Exhibition in Berlin

Before he returned to Vitebsk and Bella, in 1914 Chagall accepted an invitation to exhibit his work in the Galerie Der Sturm, Berlin. Herwarth Walden was an eminent art dealer specialising in Expressionist and Cubist art in his Berlin Gallery, it was a great opportunity for the young artist, who had been experimenting in modern styles of art.

It was Chagall’s intention to continue on to Belarus and marry Bella, then return with her to Paris to spend their lives there together.

The opening of the exhibition in Berlin was a huge success and in high spirits Chagall travelled home to Vitebsk on his three month visa, where he planned to stay just long enough to marry Bella.

First World War

A few weeks after his return home, in 1914 the First World War began and the Russian border was closed for an indefinite period, trapping Bella and Chagall in Russia, and separating him from his 40 canvases, 160 gouaches, watercolours and drawings left behind at the gallery. He was only able to recover three canvases and 10 gouaches eight years later.

Chagall’s next challenge was to convince Bella’s parents that he would make a suitable husband for their daughter. He had to demonstrate that despite being a painter from a poor family, he would be able to support her. His wish to become a successful artist now became his primary purpose and motivation.

Marriage to Bella

Joyful at being reunited, Bella and Marc were married in 1915, in their home town of Vitebsk. Soon after they travelled to Petrograd, (previously and currently, St Petersburg) to start their married life together. It was there he painted, ‘The Poet Reclining’ and several portraits of himself with Bella.

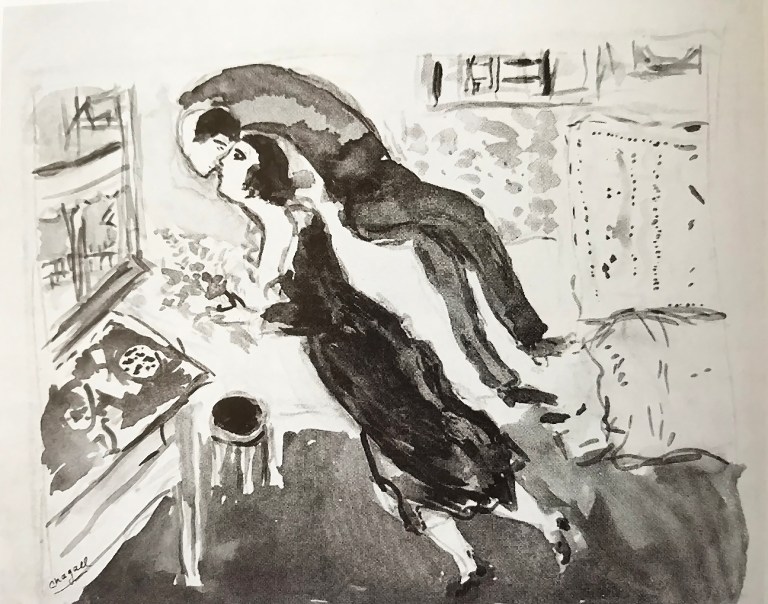

Chagall’s exhubarent love and joy was expressed in his art of that time and later often revisited. In several of his paintings he and Bella defy gravity, as if their love is swooping them up in the air as they kiss; others present the lovers flying in the moonlit sky gazing over the miniature roof tops of the town below, as one does in dreams.

Bouquets and candlesticks, whimsical birds, roosters, cows and fiddlers appear randomly within the sky or landscape. Chagall painted these in vivid colour, inspired by Hasidic fables and folklore, as well as the love of his life.

Chagall’s work was surreal but he was not a Surrealist, nor a Cubist, although he flirted with Cubism at times. He would turn down André Breton’s invitation to join the Surrealists 10 years later.

He did not want his work to be associated with any ‘ism’ or art movement, he was content with his own dreamy, idiosyncratic language, a visual feast and illogical fantasy, his uniquely modern style.

Charcoal drawing of Bella Chagall

Petrograd (St Petersburg)

Life in Petrograd during the onset of war was not ideal. The severe restrictions against Jews residing in big cities were relaxed during the war years, making it possible for Chagall and Bella to live in Petrograd legally.

Unfortunately, they could not escape the general anti-Jewish violence seething in the country.

Attacking Jews was an habitual outlet for unhappy citizens’ and soldiers’ frustration. Chagall himself barely escaped being killed one night during one such pogrom, where he saw other Jews being murdered.

Bella’s brother managed to get Marc a job as a clerk in the War Economy Office, to avoid conscription. He hated the work but got by and painted when he could.

In 1915, Chagall began to exhibit his work in Moscow. In one exhibition he was represented with 45 of his works in the avant-garde artist group ‘Jack of Diamonds’. This exposure gained him wider recognition and a number of wealthy collectors began to buy his work.

Ida is born

Within less than a year after their marriage in May 1916, their baby daughter Ida was born. Initially Chagall was disappointed as he wanted a son, but his tenderness grew and the little baby brought delight to the couple as well as warming the hearts of Bella’s parents.

However, despite the positive images that Chagall created in his art to describe marital and parental bliss, there was very little joy in the country generally that year, as Russia was in the throes of hunger and political unrest.

Baby Ida was often screaming with hunger and Bella struggled to produce enough breast milk, due to her own poor diet.

When summer came, the family went to a dacha (summer retreat) not far from Vitebsk, where Chagall’s parents were originally from and where his grandparents still lived. There they could make sure that Ida would have milk and the family could improve their healthy with the fruit and vegetables which still grew there in abundance. The country environment helped Bella to regain her strength and gave Ida a chance to thrive. Here Chagall was able paint with less disturbance and more freedom.

The Russian Revolutions

The First World War did not prevent Chagall from painting, neither did the Revolution. 1917 was an unusually productive year.

There were effectively two revolutions in 1917 Russia, the first dismantled the Tsarist autocracy and brought in a provisional government. Then alongside it arose a grassroots community known as Soviets which contended for authority.

Chagall and many Russian Jews initially welcomed the 1917 Revolution, as it seemed to bring Jews full equality of rights; segregation was ended and college admission restrictions were lifted.

However, the October Revolution lead by Lenin and Trotsky, cast a long shadow of uncertainty and chaos over Russia, a country already weakened by massive wartime human loss and food shortages.

In 1918 Petrograd was under Soviet control, the Revolution demanded new forms of artistic expression from painters, poets, composers and sculptors. Chagall had gained a reputation as a member of the modernist avant garde, which enjoyed special privileges and prestige as the ‘aesthetic arm of the revolution’.

With this new status Chagall was nominated for the post of ‘Commissar of Fine Art’ within the Ministry of Culture. Bella was not at all happy at the idea of her husband entering any political office and she urged him to leave Petrograd and return to Vitebsk where they could live comfortably in the large Rosenfeld family house, with Bella’s parents.

Vitebsk

Chagall agreed with Bella and declined the appointment, instead he acted on an idea he had about founding an art school in Vitebsk.

He detailed his idea to the minister of Culture, Anatoly Lunatcharsky, who reacted with enthusiasm. So in 1918 he set up his own ‘Free Academy of Art’, hiring important artists to teach, such as Ivan Puni, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich and Yehuda Pen. His Academy would become the most renowned school of art in the Soviet Union.

In September 1918, to the irritation of Bella, Chagall was officially appointed by Lunatcharsky as ‘Fine Arts Commissar’ in Vitebsk. He was now responsible for museums, exhibitions, art schools, lectures and all other art activities. He devoted himself to his duties wholeheartedly and was constantly pestering the authorities for more resources for his art school projects.

Chagall wanted to create a collective of independently minded artists each with their own unique style to inspire the students. This would soon prove to be difficult as two key members of the art school were keen endorsers of ‘Suprematist Art’. This was an abstract art often excluding colour, based on lines, squares and circles, to capture “pure artistic feeling”, rather than visual depiction of life or objects; it was quite remote from nature or expression and did not engage Chagall.

To celebrate the first anniversary of the October Revolution, Chagall organised artists and craftsmen of the Academy to decorate the town, he wished to bring art to the people. Communist officials were not impressed and asked what do green cows and flying horses have to do with Marx and Lenin ?

Kazimir Malevich disapproved of Chagall’s art, calling it “Bourgeoise individualism”. Chagall felt betrayed and hurt by his friend, Lissitsky who joined his opponent, Malevich in his theoretical teaching of the “death of painting”, a phrase included in the ‘Suprematists’ manifesto.

In 1919 heated debates between Chagall and Malevich became eruptive, Chagall decided to resign from the Vitebsk Academy, which by now had been renamed by Malevich as the ‘Suprematist Academy’. With bitter disappointment Chagall and his family left Vitebsk for Moscow.

Moscow and the Jewish Theatre

Like Bella, who loved theatre and had originally wanted to be an actress, Chagall was very interested in the world of theatre. In late 1920 Chagall was offered work as stage designer by Granovsky for the newly formed State Jewish Chamber Theatre in Moscow. While the family lived there Bella found the opportunity to reignite her love for the theatre and acting.

Chagall enjoyed this relatively brief time working on several huge murals over 7 metres long and nearly 3 metres high. He created various lively Yiddish scenes for humorist, Sholem Aleichem’s one act plays, including in them his characteristic dancers, fiddlers, acrobats and farm animals. Bella would sometimes watch him at his work, while he painted the stage sets, curtains and ceiling for the small auditorium.

In his sets Chagall emphasised the illogical and fantastic, inventing a store of symbols and stylised design that reflected ordinary Jewish life in dramatic form. His work was ‘theatre’ itself, and was central to the Chamber Theatre’s success.

These murals would later come to represent a landmark in the history of the theatre, but at the time not all theatregoers approved of Chagall’s creations. He was accused of caricaturing the Jewish character and encouraging anti-Semitism. Also along with other artists and leftists, he again fell into disfavour with Soviet officials, who claimed he and the actors ‘danced and sang’ in their theatre, with complete disregard for the misery throughout the land.

The catastrophic damage to the economy of the war years and the inability of the 3 year old Soviet Republic to provide food and stability after the Revolutions, lead to widespread famine. In Moscow and Petrograd there were bread riots, many of which would erupt into anti-Jewish pogroms.

In 1921 the Chagall family found it necessary to move to Malakhovka, a smaller, less expensive town outside Moscow. Here, when Chagall wasn’t commuting to Moscow to work in the Theatre, he taught drawing at a Jewish boys shelter. The shelter housed orphaned refugees from Ukrainian pogroms. The refuge was a centre for many Yiddish writers including Der Nister, who lived with Chagall and his family for a short while.

As the new Soviet state took shape, the Chagall family, who had been living the past year in primitive conditions, started to face artistic restrictions and the threat of starvation. Chagall and Bella decided they should aim to find a better life in France, where he could develop his art and Bella and Ida would have a more stable and comfortable way of living.

While waiting for the uncertain approval of an exit visa, Chagall found time to start writing his autobiography. He was never paid for his dedicated and wonderful work at the Jewish Chamber Theatre.

Leaving Russia

In 1922, Chagall, Bella and their five year-old daughter, Ida, left Russia, never to return. First they emigrated to Kaunas, Lithuania, where Chagall had managed to arrange with the Lithuanian ambassador in Moscow, to send ahead 65 of his paintings as diplomatic baggage. After a short stay in Kaunas, Chagall continued with his paintings to Berlin, where he had hoped to find Herwarth Walden of Der Sturm Gallerie, but to no avail.

From summer 1922 until the autumn of 1923, Chagall and his family stayed in Berlin, where eventually Chagall found only 3 of his numerous ‘lost’ paintings. The money owed to him by Walden had been left with a lawyer, but due to the ravages of inflation it amounted to next to nothing at the current value of the German mark. However Walden had continued to exhibit and promote Chagall’s work in his eight year absence, and although he gained nothing financially from his paintings his reputation had grown extensively in Western Europe.

During their time in Berlin Chagall was introduced to graphic art and produced his first etchings and engravings.

Paris

In early 1924, the Chagall family started their new life in Paris, at 36, Avenue d’Orleans. Chagall was appalled to find that 150 of his works left in his old studio in 1914 had been taken or thrown out by the concierge, and refugees were now living there. With all his early works now lost, Chagall began painting from his memories of the early years in Vitebsk. He painted replicas of many of his lost or stolen works, not for financial reasons but to preserve them as images, like chapters of a diary of his life.

In Paris Chagall met Ambroise Vollard, a publisher and French art dealer, with whom he formed a new business relationship. Vollard commissioned Chagall to illustrate several books, including 30 gouaches for ‘La Fontaine’s Fables’, and etchings for ‘The Seven Deadly Sins’ and ‘Motherhood’. Also Vollard commissioned Chagall to paint a series of works based on the circus.

Chagall’s first retrospective took place in 1924 at the Galerie Barbazanges-Hodebert, Paris, where he exhibited 122 art works and became acquainted with painters Juan Gris, Georges Rouault, Maurice de Vlaminck and Pierre Bonnard. His success and prominence in artistic circles brought him some financial freedom at last.

Bella the loving support

By 1926 the family were living in Boulogne-sur-Seine, a western suburb of Paris. Chagall, Bella and Ida were now able to travel and explore different parts of France, the Côte d’Azur as well as visit Spain, Holland and Italy. It was the family life they had dreamed of.

The paintings made by Chagall in this period were bright and joyful, inspired by; “rich greenness—the like of which I had never seen in my own country”, and the “throbbing light”.

Inspired by the light and countryside of southern France, Chagall also discovered the charm of flowers, (apparently not knowing of ‘bouquets’ in Russia). He painted them as if they were a landscape, often with Bella and himself reclining amongst the petals. In Chagall’s mind flowers were a spiritual link to the universe and formed part of his artistic language.

In 1926 Chagall had his first exhibition in the United States at the Reinhardt gallery in New York, he did not attend the opening, preferring to continue with his painting on the Mediterranean coast near Toulon.

While Chagall painted, Bella was raising their daughter and supporting his career.

In 1931 Bella translated Chagall’s biography, ‘My Life’, from Russian into French, after another linguist had failed to understand the nuances of Russian humour and poetic nostalgia, not meeting Chagall’s approval.

From February to April 1931 Chagall travelled with Bella and Ida to The Holy Land, having been commissioned by Vollard to illustrate a new edition of the Bible. Through Egypt, Syria and Palestine Chagall made sketches and paintings which took on a more melancholy expression, almost as if having a sense of foreboding of what would manifest in the next decade.

In 1934 Ida aged 18 married a young lawyer, Michel Gorday.

Chagall’s painting, ‘The Betrothed’s Chair’ which commemorated the occasion is poignant in its’ omission of the wedded couple, its emptiness speaking of sadness rather than happiness or joy.

In 1935 after travelling to Poland for the opening of the Jewish Cultural Institute in Vilnius, it became more clear to Chagall that there was a real threat to the Jewish population.

The Nazis had begun their campaign against modern art as soon as they seized power in 1933. Abstract, cubist, expressionist, surrealist art, or anything foreign, Jewish, intellectual, socialist or difficult to understand was targeted and confiscated or destroyed. Several works by Chagall were publicly burned at the Kunstthalle in Basle Switzerland, and all Chagall’s works were removed from German museums in 1937.

Once the German press had ‘swooned over him’, but the new German authorities now made a mockery of Chagall’s art, describing it as, “green, purple, and red Jews shooting out of the earth, fiddling on violins, flying through the air”, representing an ‘assault on Western civilisation’.

By now Chagall had finally gained French citizenship, he had tried four years before but failed, due to having been a Soviet arts commissar.

Second World War

In 1938 Chagall decided to move his family to the relative safety of Saint-Dyé-sur-Loire, south of Orléans. With the help of his daughter Ida, Chagall moved his paintings from his Paris studio to their new home for security. In September 1939 war was declared and France was invaded, Chagall continued to paint, still unaware that French Jews and other victims of the Nazi regime were being sent to concentration camps and oblivious of the atrocities taking place.

On the advice of fellow artist André Lhote, in autumn 1939 Chagal and his family moved to Gordes, a village commune in the Luberon Valley just north of Marseilles, in the unoccupied South of France. They bought an old school house which served as a home and studio, where they lived contently for a year.

Paris Invaded

It was not until October 1940, when Paris had been taken by Hitler’s army, that Bella and Chagall finally appreciated the danger they faced. Jewish professionals were being removed from public and academic positions of office. Many well known Russian and Jewish artists were seeking to escape to America, these included Max Beckmann, Max Ernst and Andre Masson. Others like André Breton and Fernand Léger had already departed.

Chagall and Bella’s daughter Ida understood the urgency, she persuaded Alfred Barr of the New York Museum of Modern Art to add Chagall’s name to the list of prominent artists whose lives were at risk.

In the winter of 1940 Chagall and Bella were visited by Varian Fry, with an invitation from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to come to the United States.

Varian Fry, an American journalist and director of ‘Emergency Rescue Committee’ and Harry Bingham, the American Vice-Consul in Marseilles, ran a rescue operation to smuggle artists and intellectuals out of Europe to the United States by providing them with ‘Nansen passports’, a form of identity for stateless people. Chagall and Bella were two of over 2,000 who were rescued by this operation.

New York

After leaving Marseilles on the 7th May and changing ship at Lisbon, Chagall and Bella arrived in New York on 23 June 1941, the day after Germany invaded Russia. From afar Bella and Chagall observed in shock and dismay as the Jewish homeland of their youth was systematically destroyed first by the Communists then by the Nazis.

Ida and her husband later followed her parents on the renowned refugee rescue ship SS Navemar, bringing with them large crates of Chagall’s work. SS Navemar was notorious because it had previously been a cargo ship that carried coal, with bunks fitted in the filthy cargo hold. Although there had been attempts to clean the ship, time was too scarce to complete the job. The task and responsibility of transporting her father’s work was an intense and stressful one. The crates were impounded on route to Lisbon in Spain and it took 5 weeks for Ida, with the help of the American Embassy and her French and Spanish friends, to release the consignment for its’ journey onto America.

Upon disembarking in New York, Marc and Bella Chagall were greeted by Pierre Matisse, art dealer and son of Henri Matisse and few old friends who had already emigrated. They were initially overwhelmed by the city, Chagall describing it as a ‘Babylon’. He discovered that he had already achieved an international reputation there and initially he felt uncomfortable with this role, in a foreign country, whose language he could not yet speak.

Before long Chagall and Bella found an apartment in East 74th Street Manhattan and began to settle in. Days were spent visiting galleries befriending other artists and discovering the Jewish quarter, in Lower East Side, where Chagall could enjoy reading the Yiddish press and eat Jewish food.

In November 1941 Chagall had his first exhibition at Pierre Matisse’s New York Gallery, showing 21 paintings from the years 1910-1941. Pierre became Chagall’s representative in the United States, paying the artist a generous monthly advance for his work. Due to the exhibition’s success Chagall was commissioned by choreographer Léonide Massineto design sets and costumes for the New York Ballet Theatre’s company’s production of Pushkin’s ‘Gypsies’.

While Chagall had done stage settings before in Russia, this was his first ballet and it would give him the opportunity to visit Mexico City where the production was to be transferred. Bella and Chagall were enthusiastic about Mexico and the work. While Chagall painted four large backdrops, Bella and a team of Mexican seamstresses made the ballet costumes.

At the premier, famous mural painters Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco were in the audience, the ballet received tumultuous applause and Chagall was called up on to the stage repeatedly to resounding ovation. He was the hero of the evening. His triumph reoccurred when the ballet opened four weeks later in the Metropolitan Opera, New York.

Unlike Chagall, who was immersed in his work and popular with friends, Bella was unhappy in New York, she felt lonely and missed Paris. Added to this the couple had learned more about the German invasion and the eradication of the Jewish population in Vitebsk, as well as the horror of the concentration camps.

In the summers of 1943 and 1944 the Chagall family holidayed in Cranberry Lake in upstate New York, where Chagall painted village scenes and Bella could walk in the countryside.

In the September of 1944 as the family were planning to return to New York Bella contracted a throat infection with a fever. She was taken to a nearby hospital which could not treat her, as it had no antibiotics due to the wartime shortage of medicine. Bella died a few days later, aged 49.

Chagall’s eternal muse

Bella’s sudden death was a huge blow to Chagall, he could not work for many months, devoting himself instead to illustrating Bella’s book, ‘The Burning Lights’, a love letter to their native town to Vitebsk, which she had completed a few days before her death. The two books were published in 1945 and 1947, lavishly illustrated by her husband and later translated into several other languages.

Bella had been married to Chagall for 29 years and had stood by him through good and bad times, sharing his sorrows and his triumphs. She had been his only lover and muse as well as his sincerest critic, his truest friend and loving mother of their only daughter, Ida.

During the entirety of their relationship, Bella was a constant source of inspiration for Chagall, appearing in hundreds of canvas’s. Although Chagall married again, Bella continued to be his muse for for the rest of his life.

OTHER 20TH CENTURY MUSES BY MARINA

LYDIA DELECTORSKAYA MATISSE’ MUSE

MARIE-THÉRÈSE WALTER PICASSO’S MUSE

DORA MAAR SURREALIST

EMILIE FLÖGE KLIMT’S MUSE

FRIDA KAHLO MUSE

TEHA-AMANA GAUGUIN’S MUSE

WALLY NEUZIL EGON SCHIELE’S MUSE

Jeanne Hébuterne

Acknowledgements and further reading:

Chagall: A biography by Jackie Wullschläger A Knopf 2008

Chagall, Jacob Baal-Teshuva Taschen 1998

Chagall, Susan Compton, Royal Academy of Arts/Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London 1985

Marc Chagall My Life, autobiography Penguin Books Ltd, 2018

The Flying Lovers, Bella and Marc Chagall

The Story of Chagall, as Told by His Granddaughters

Head over heels in love: Marc and Bella Chagall

Marc Chagall’s struggle with fatherhood By Galya Diment

Byron’s Muse : Chagall- The Colour of Love

Dear Marina Elphick, Love your work. Charmante. Perhaps you might be interested in taking a look at the volume on Edouard Vuillard published in 2012.* The “intimiste” par excellence that was Vuillard had many muses in addition to his dear mother. They included Marcelle Aron, Lucy Hessel, and “la reine de Paris,” Misia Godebska, elle-meme. The latter, the eponymous heroine of a show at the Orsay, later during the same year. *Stephen Brown, Edouard Vuillard, New York, New Haven, and London: Jewish Museum, Yale University Press, 2012.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an amazing site. You have done so much research on Chagall. Your work is brilliant. I , like others, am so glad I stumbled on your work.

Kurt Sorensen

LikeLike

Thanks for visiting my site, I am glad you like it! The research takes a long time but I enjoy discovering more about my favourite artists and this muses. I am a creative person rather than an academic, but the research keeps me inspired 😉.

LikeLike

Marina, this is fab! Long time, no see – must catch up soon and in the meantime hope that all’s well. Love Gill xx

LikeLike

Hi my talented darling daughter.

What a great posting on Chagall and his muse and wife Bella. You never seize to astound us with your wonderful muses and the fascinating text, that obviously takes a lot of research and work to write. I had not seen the majority of paintings by Chagall nor had I had any insight of Chagall’s life as a Jew in Russia and the restrictions that were imposed on Jews, even before the post war persecutions.. Well done again, Marina, we are immensely proud of you and love the portraits of Bella. Speak to you soon, Love from Mum and Dad xx

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I’m so happy I stumbled across this in checking a reference to “Bella” — a poem written by an unpublished poet. I’d add it here, but I do not own it. This is a lovely way to explore the lives of Marc and Bella — and I see there are other such histories. I must check them all! –Andra Miller

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Andra I am glad you stumbled upon my muse and liked Bella. There are many lesser known stories, of the lives of women behind the great artists. Making my muses are a way to bring some of those‘herstories’ to life.

LikeLike